The Measure Of Success

For this small job shop, measuring and controlling everything are the keys to lean—very lean—manufacturing. Yet its management style is surprisingly open and trusting.

"People’s lives are at stake in everything we do,” says Don Garrity, founder and CEO of Garrity Tool Co. in Indianapolis, Indiana. This 20-person job shop specializes in close tolerance machining for the aerospace, defense, automotive and medical industries. Jobs range from a single prototype or piece of gage tooling to production runs exceeding 100,000 pieces. Almost all of these workpieces are critical components that could determine whether a medical procedure succeeds in saving a patient’s life, whether a weapons system functions properly and allows a jet pilot to complete a mission, or whether the steering system on an SUV will keep a young family inside safely on the road.

This life-or-death reality is the main motivation for Mr. Garrity’s intense preoccupation with controlling every aspect of the manufacturing process to ensure compliance with specs and tolerances. “Lives are at stake,” he says.

Controlling every aspect of the manufacturing process is also the key to the shop’s ability to be both competitive and profitable. Mr. Garrity fully understands that his shop must continually find ways to machine parts “better, faster and cheaper.” That is also a life-or-death reality for his business. His shop’s existence is at stake.

Yet Mr. Garrity is certainly not the kind of manager his employees would characterize as a “control freak.” “If you have good people, they can and should make as many of their own decisions as possible,” he says. “That means giving them the right information, then trusting them to make good decisions.” As clear evidence that this approach is working, Mr. Garrity points out that the shop operates with virtually no supervisory staff, giving it a flat and “fat-free” management structure. Every employee, from the manufacturing engineers to machine operators to the truck driver, has authority to make his or her own purchases, for example. Machine operators requisition their own cutters and tooling items—whatever they need to hit production goals.

Of course, Mr. Garrity and his partners have their own key decision-making responsibilities. “We have to know how best to serve our customers. That means we have to have the right information to make good decisions, too,” he says.

"Everybody makes good decisions because they get good information,” Mr. Garrity explains. “And they get good information because we measure every measurable aspect of each process.” Of course, workpiece dimensions and other attributes are measured, but so are tool life, machine uptime, cycle time, setup and changeover time. This data is collected, analyzed and shared in a very timely and highly visible manner, largely due to the efficiency of the company’s shopfloor control system. Garrity Tool Co. uses the E2 shop system from Shoptech Industrial Software Corporation (Glastonbury, Connecticut).

Lessons In The Navy

Don Garrity learned a lot about the importance of lean manufacturing before he started his own manufacturing company. He began his career as a mold maker, doing stints in the toolroom at a Ford plant in Indianapolis before joining the Naval Avionics staff as a machinist. He worked his way up to the toolroom, then to tool design, and then to the job as contract monitor. For 5 years or so, he traveled around the country visiting aerospace companies and their subcontractors as a contract monitor for the U.S. Navy. “This gave me a chance to see what leading shops were doing—or shouldn’t be doing,” Mr. Garrity recalls. All the while, he kept his own machining skills fresh by making tooling for a few local customers in a small shop he maintained in his garage.

The highlight of his career with the Navy was being part of the team that codified the best manufacturing processes in the effort to reduce the cost of producing today’s high-tech jet fighters. The result was a book called Breaking The Cost Barrier, published in 1999. Not only did Mr. Garrity help define the concepts outlined in this book, but he also proved the value of this approach to lean manufacturing by successfully implementing the underlying principles in his own job shop, which he incorporated as Garrity Tool Co. in 1995 with his partners Dwight Griggs and John Entwistle.

One of his goals in starting this company was to create an environment most like the one he himself would want to work in as an employee. “It had to be lean but not mean,” he says. “I wanted pride in ownership to be a part of every employee’s experience—that means giving people the responsibility to work to the highest quality standards yet be fully cross-trained to handle jobs through every step of the manufacturing process.”

The shop grew rapidly, doubling in size every year for the first 4 years. Since then, the shop’s sales have grown 15 to 18 percent a year, while holding steady at around 20 employees.

Information FOR The Shop Floor

The shop’s use of shop control software is a particularly telling way to see how the shop balances decentralized decision making with the need to have thorough control of the manufacturing process. It all starts with the routing, scheduling and estimating modules in the shop software system. Mr. Garrity’s partner, John Entwistle, does most of the data entry at this point. Because this system is fully integrated, entries in the estimating module flow into the job orders module and then into the scheduling module without rekeyboarding data. When the job is released to the shop, paper travelers and other documents can be produced with a few keystrokes. Purchase orders for raw material or tooling items can also be prepared almost instantly, as can requests for quotes to subcontractors for heat treating, anodizing and so on.

Mr. Entwistle uses the routing module to create a detailed list of processing steps. This is essentially a process plan. However, it includes all actions related to quality control procedures. What to measure, when to measure, how to measure, how to document the results and what to do about them are all detailed. This is important because it allows the shop to monitor the cost and efficiency of this essential aspect of manufacturing.

The estimating module allows Mr. Entwistle to attach time standards to each operation, including inspection routines. The idea is to create realistic targets for accurate scheduling and to benchmark shop performance. It is NOT used as a prod to make the operators hustle.

Scheduling is the next step. Here, the system’s flexibility comes into play. In some cases, it is appropriate to schedule a job for a department and in other cases to schedule it for an individual machine. For example, the shop has two rows of Haas vertical machining centers facing each other in the center of the shop. By scheduling these machines as a department, workpieces can be shifted from machine to machine to maximize workflow. On the other hand, the shop has several 50-taper horizontal machining centers, such as a palletized Mazak Mazatech H-500/50, which are scheduled as separate workcenters. Because inspection procedures are never an afterthought, it is significant that the shop’s Mitutoyo Bright A707 computer controlled coordinate measure machine is scheduled like any other workcenter.

The system allows the shop schedule to be viewed in several ways. Planners can spot bottlenecks and see their impact on delivery dates. What-if scenarios can be explored. Garrity Tool normally works one-shift attended, but to satisfy customer needs the shop will add overtime or a second shift with consent of the workforce. All of the modules in the E2 system are integrated, so when a process plan is modified in the routing module, for example, the schedule is also revised. Alerts are issued if the new schedule shows that workcenters will be overloaded of if critical dates will be missed.

Here’s a key point. Mr. Garrity doesn’t expect the shop system to straitjacket the machine operators. When a job is released to the shop floor, its routing is meant to be viewed as a road map. Operators are still responsible for final decisions about machining strategies, tooling, CNC programming and setup, all of which are documented and kept on file. However, the traveling router that accompanies the workpieces on the shop floor makes it clear exactly how workflow is to proceed from process to process. This ensures that minimal delays are encountered on the way.

Operators record time per job and time per operation with a bar code reader at the end of the day in a batch mode. Bar codes are generated by the shop software system for each job. Bar charts representing each workcenter and each employee are posted at the bar code reader, so that information is also scanned in to further automate data collection. The master shop schedule is then revised daily to reflect current conditions.

Information FROM The Shop Floor

Although the shop system is not used to infringe on the decision-making responsibilities of the machine operators, it is used very effectively as a decision making tool on the planning level. Again, the ability to get good information is the key. Various reports that can be prepared from the data collected in the system give Mr. Garrity and his partners a clear and current picture of what is happening in the shop, based on the comprehensive set of measurements about each step of the manufacturing process. As Mr. Garrity is fond of saying, “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” He and his partners use these reports to find ways to improve efficiency and reduce costs.

Job Cost Summary, for instance, is one of the reports that Mr. Garrity and his staff study closely. This screen provides a cost breakdown of a completed job, showing the costs associated with each activity or material associated with that job. Analyzing this report helps the shop identify problem areas or find opportunities for improvement.

For example, one job that ran on the 40-taper vertical machining centers revealed that 10 percent of total costs were related to the number of end mills consumed. The workpiece material was an exotic stainless that required frequent tool changes to meet dimensional tolerances. Because the workpiece was relatively small, it seemed suited for the 40-taper machines. On analysis, spindle deflection was suspected as the cause of excessive tool wear. A test part was machined with the same style of end mill and tool path but on one of the shop’s 50-taper machines.

This machine had a more rigid spindle, and tool life improved dramatically. Running the same job on this machine would reduce tooling costs by 40 percent. “We went back to the customer and quoted them a lower figure on a repeat order for that workpiece,” Mr. Garrity says. The job did repeat, and the shop found that the larger machine also could handle higher speeds and feeds and still hold tolerances. This change reduced cycle times. Altogether, switching to the 50-taper machine resulted in a 25 percent cost reduction.

The Job Performance Summary allows jobs to be compared on the basis of setup time, inspection time, tooling usage and so on by operator. For example, if one operator’s setup time appears to be excessive, Mr. Garrity looks for the root cause. Perhaps the operator needs additional training. It’s just as likely, however, that exceptionally fast setup times will show up, and in that case the operator may have an effective shortcut to share with the rest of the staff.

Likewise, Workcenter Utilization is another summary report that guides important decision-making. For example, the shop can look at how many hours each machine has been used over a given time period. This report helps identify equipment needs and determine when acquiring another machine is justified. Monitoring this data led the shop to purchase two new machining centers in January 2002, at a time when few shops were adding capacity. Garrity Tool invested close to $500,000 on these machines. They have been moneymakers ever since.

Although Mr. Garrity acknowledges that the Windows graphical interface used by the shop system makes these reports easy to format and customize, he notes that the quality of the data is what really counts. “If we didn’t insist on a consistent and disciplined approach to data reporting, these summaries wouldn’t give us reliable, current information. Likewise, if we didn’t measure cycle time, inspection time, setup time and so on, these summaries would not be nearly so effective as a management tool.”

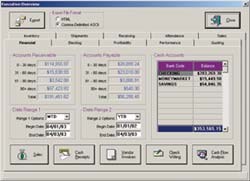

The system report that Mr. Garrity finds especially useful is the Executive Overview. “This module gives me a picture of the health of the business,” he says. This module combines financial data with shop data. With a mouse click, the Executive Overview shows Accounts Receivable and Accounts Payable. He can click to the bank balance sheet to spot and head off impending cash flow problems. Mr. Garrity can check the company’s backlog by vendor, by industry and by workcenter.

“The bankers love it too.” Mr. Garrity says. Data from the Executive Summary has helped the shop secure financing to support its growth. “We can tell customers that our shop is as big as they want us to make it to meet their needs,” Mr. Garrity says. In one case, for example, the shop was ready to lease new space for a new line of screw machines to handle a customer’s contract for a high-volume part order. “Getting the loan to back this new business wouldn’t have been a problem because we could easily document the projected return,” he says.

Quality Council

Mr. Garrity and his partners meet formally once a week as a Quality Council. Together, they review the shop’s delivery and quality performance rating as measured against the ultimate goal of zero defects to customers and 100-percent on-time delivery. Every nonconformance (missed delivery data, defect from supplier, defect to customer) is analyzed to determine its cost to the shop, its cost to the supplier, and its cost to the customer. Each nonconformance remains an open agenda item until the root cause has been identified, a corrective plan implemented, and positive results reported. Data to support all of the Quality Council’s activities are derived from the shop software system. It is not unusual for members to call up data in the system during the meeting.

The Quality Council also monitors all Requests For Information, a discipline that streamlines critical communication with customers. (See sidebar.) Finally, the Quality Council identifies discussion items for monthly “All Hands” meetings. These meetings bring every employee together to review performance ratings, establish training priorities and schedules, and discuss company strategy. Among other things, employees get an idea of how the company is doing overall, with the reassurance that their jobs are safe and that the company is on a sound path.

No Boundaries

Although Garrity Tool relies on its shop software to provide critical information for the shop floor as well as from the shop floor, it would be a mistake to think that there is some division between these uses. “We’re talking about two sides of the same coin here,” says Mr. Garrity. “Or two sides of a flat organizational structure, to put it another way,” he adds. One of the chief values of an integrated shop software system is that it helps break down boundaries that hinder organizations with rigid hierarchies.

“No boundaries” is also how Mr. Garrity likes to characterize this job shop’s flexibility and versatility. Few shops are able to handle such a wide range of precision machining work, from one-offs and prototypes to volume production of workpieces the size of an engine block. Many shops avoid such variety because it is hard to manage, so they stick to one kind of work they are comfortable with. Mr. Garrity calls such thinking “self-limiting” and the wrong kind of thinking for growth. “We’ll take on jobs that push our flexibility. We’re not afraid to try new things,” he says.

This works because 1. the shop has a variety of machine types, 2. the shop has a full cross-trained workforce and 3. the shop knows its “measure it/manage it” approach is effective.

Mr. Garrity sums it up, “For us, lean manufacturing means there no boundaries on the ways the company can grow.”

Related Content

What Are the Limits to Make-to-Order Manufacturing?

Automated storage and retrieval system maker Modula produces a product with 2,000 parts and hundreds of variations that has to be completed within a customer’s site. Here is a picture of what is possible in making a product tailored to the customer.

Read More10 Lean Manufacturing Ideas for Machine Shops

In addition to the right mix of traditional strategies, a lean manufacturing toolkit can make high-mix, low-volume machining faster, more predictable and less expensive.

Read MoreRead Next

3 Mistakes That Cause CNC Programs to Fail

Despite enhancements to manufacturing technology, there are still issues today that can cause programs to fail. These failures can cause lost time, scrapped parts, damaged machines and even injured operators.

Read MoreThe Cut Scene: The Finer Details of Large-Format Machining

Small details and features can have an outsized impact on large parts, such as Barbco’s collapsible utility drill head.

Read More

%20and%20Don%20Garrity.jpg;width=860)

.png;maxWidth=300;quality=90)