Waterjet Cutting Without Abrasives

Soon, industrial users of waterjet metalcutting may be able to cut sheet metal, composites and other materials without abrasives -- or at least with much less abrasive than they're accustomed to using.

In conventional waterjet metalcutting operations, abrasive material is metered to the jet stream to enhance the cutting action. Soon, however, industrial users of this technology may be able to cut sheet metal, composites and other materials without abrasives—or at least with much less abrasive than they’re accustomed to using.

Flow International Corp. (Kent, Washington), a major manufacturer of waterjet cutting equipment, is experimenting with waterjet cutting at elevated operating pressures with little or no abrasive as an alternative to waterjet cutting with the levels of abrasive currently used in industry. “The abrasive material is a big expense item, accounting for 60 to 65 percent of total operating costs for the waterjet cutting process,” explains Dr. Mohamed Hashish, Flow’s senior vice president of technology. “Our experiments indicate that by increasing waterjet cutting pressures, we may be able to significantly reduce the amount of abrasive used and, for some applications, eliminate abrasive altogether, improving the competitiveness of the process.

“Operating pressures for the waterjet cutting process have increased from 35,000 psi in the early 1970s, to 60,000 psi today,” Dr. Hashish continues. “Our company recently introduced a commercial machine capable of operating at 87,000 psi, and in our lab we are experimenting with cutting at pressures up to 100,000 psi. Obviously, the tubing, fittings, seals, cylinders, pressure vessels and other components of such a system must be designed for such pressures.”

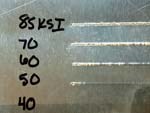

The test strips in the illustration below, produced in Flow International’s lab, show the effect on sheet metal being cut without abrasive as water pressure is increased. The first pass at 40,000 psi on the 0.025-inch-thick aluminum test strip merely etches a line in the strip. Results are about the same at 50,000 psi. Breakthrough occurs at 60,000 psi but is not sustained. Intermittent cutting occurs at 70,000 psi. It takes 85,000 psi to produce a continuous cut in the test piece. (All passes were made at 350 ipm.) Results are similar for the brass test strip: intermittent breakthrough first occurs at 70,000 psi, and continuous cutting does not happen until 85,000 psi. (All passes were made at 80 ipm.)

“If we can eliminate the use of abrasives for some classes of materials, such as thin sheet metal and composite materials, we can reduce operating costs substantially,” Dr. Hashish explains. “Even where abrasives cannot be eliminated entirely, usage can be significantly reduced, still providing a substantial savings.”

Thin aluminum and brass sheet were not selected as test materials by accident. “Lasers are being used increasingly to cut sheet metal, but they do not cut aluminum and brass as efficiently as they do other metals,” Dr. Hashish observes. “Waterjet cutting with little or no abrasives gives processors of these metals a viable, and now increasingly cost-effective, alternative to lasers and other sheet metal-cutting processes.

“The ability to use the waterjet with little or no abrasives expands the user’s processing flexibility as well,” Dr. Hashish continues. “For example, waterjet cutting without abrasive usually results in a burr (discernable on the test strips—ed.). By adding a small amount of abrasive, the user can instead get clean, burr-free cuts. The user has a choice in such cases: if the waterjet-cut part is to be deburred in a downstream operation, the user can cut it without abrasive to reduce processing costs; if the part will not be deburred, the user can cut it using a small amount of abrasive to get clean, burr-free edges. The user can use the process with or without abrasive as circumstances dictate.”

Dr. Hashish sees the development of abrasiveless waterjet cutting at elevated pressures extending the process into areas where it has not been competitive in the past. “When we cut at the higher pressures, we’ll be using finer grits in narrower streams that will permit acceptable cutting rates with better edge finishes,” he asserts. “That will make the process more precise and even more competitive with laser cutting.”

Dr. Hashish predicts that waterjet cutting with little or no abrasive will appeal to sheet metal processing firms, aircraft and aerospace firms, and electronics firms. He stresses, however, that its use will be more application-driven than industry-driven, particularly applications where cleanliness—the complete absence of trapped or residual abrasives—is essential.

Related Content

Buying a Lathe: The Basics

Lathes represent some of the oldest machining technology, but it’s still helpful to remember the basics when considering the purchase of a new turning machine.

Read MoreInside an Amish-Owned Family Machine Shop

Modern Machine Shop took an exclusive behind-the-scenes tour of an Amish-owned machine shop, where advanced machining technologies work alongside old-world traditions.

Read MoreGrinding Wheel Safety: Respect The Maximum Speed

One potential source of serious injury in grinding comes from an oversight that is easy to make: operating the wheel in an over-speed condition.

Read MoreChoosing Your Carbide Grade: A Guide

Without an international standard for designating carbide grades or application ranges, users must rely on relative judgments and background knowledge for success.

Read MoreRead Next

The Cut Scene: The Finer Details of Large-Format Machining

Small details and features can have an outsized impact on large parts, such as Barbco’s collapsible utility drill head.

Read More3 Mistakes That Cause CNC Programs to Fail

Despite enhancements to manufacturing technology, there are still issues today that can cause programs to fail. These failures can cause lost time, scrapped parts, damaged machines and even injured operators.

Read More

.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)

.png;maxWidth=300;quality=90)

.jpg;maxWidth=970;quality=90)