Machining and Fabrication Teams are Different—Here Is How to Manage Them

The leaders of a company providing both job-shop-type machining and fabrication of custom structures describe how they respect both of these teams and how they bring them both together. ISO certification has proven to be one valuable factor.

When I spoke with Chad and Lindsey Carr recently about ISO 9001 certification, they had not yet seen much from it. No commercial impact, that is. Their shop, Engineered Fabrication, pursued and won the certification last year. So far, it has not brought any new business or opened any doors that weren’t already open to this Watkinsville, Georgia, contract manufacturer.

And Chad, the owner and president, is entirely fine with that.

New business is what any active company generally wants, of course. He hopes and expects the ISO certification to help in this. But he had no current customers that were pushing him to get certified in this way, and he was aware of no prospective customers denying him business because of the lack of this certification. Instead, he pursued it as way of establishing an externally enforced standard that the shop would adhere to and improve upon. Plus, he pursued it because the shop was ready.

“I felt like we were already doing the sorts of things, holding to the sort of process consistency, that ISO requires,” Mr. Carr says. But that was only a feeling. “If we did ISO, it would prove we were the shop I felt we were, and it would also make us better.”

Operations Analyst Lindsey Carr (his daughter) oversaw the ISO effort. Defining and documenting the shop’s processes and establishing the documentation procedures that would allow the shop to be certified was essentially a full-time job of hers for about six months. Fortunately, prior to this, she had already done some of the necessary foundational work. In 2013, she led the shop’s effort to install and transition to an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, Exact JobBOSS, for management of the shop’s work and resources. Because of the implementation of this software and the habits it requires, the shop’s staff of 29 employees had already become accustomed to tracking critical performance data. The ISO effort felt a lot like a continuation of the ERP effort, she says.

And in this shop, both of those efforts required her, and required Mr. Carr as well, to face and work with one of the defining characteristics of this particular manufacturing business that separates it from many other shops. Namely, Engineered Fabrication combines both CNC machining for repetitive part making and custom one-off fabrication within the same company. It devotes roughly equivalent staffing and resources to both. On many jobs, it employs the two capabilities in tandem. The challenge in all of this is that machining and fabrication are characterized by different mindsets and follow different rhythms, requiring management to think about them in different ways.

Weldment Workpieces

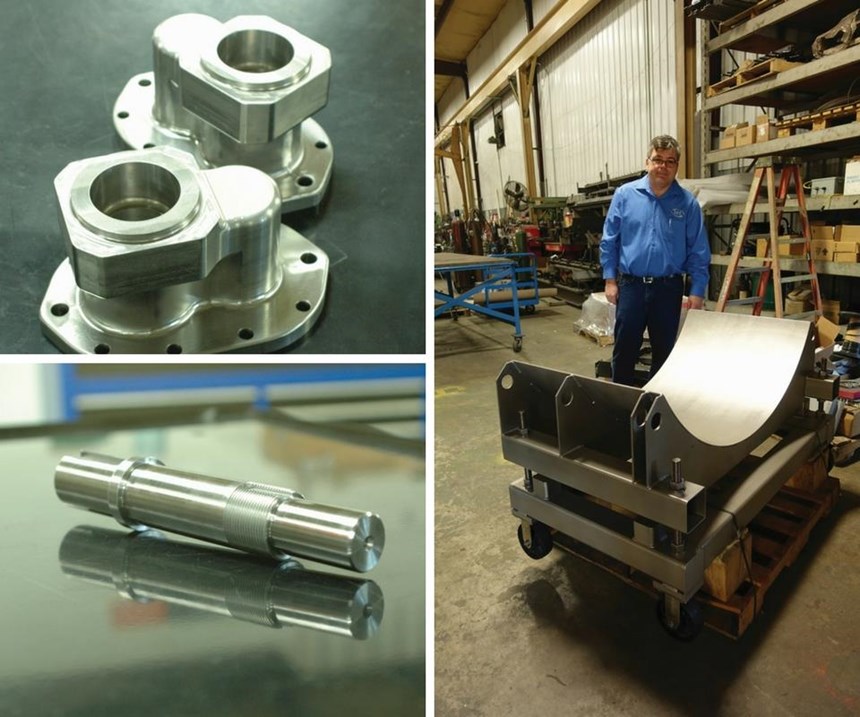

Mr. Carr helped to bring about the increased importance of CNC machining in the company. He joined in 2010 as an employee, the general manager. The company’s business then was serving OEM customers with tailor-made fabrications—fixtures, machine components, dedicated carts and other custom industrial structures—that are built largely by welding metal components. The in-house milling and turning capability at that time simply made custom parts to support this fabrication. As GM, Mr. Carr added more CNC machine tools, and sought to expand and balance the company’s business by pursuing job-shop-type piece-machining work as a complement to the fabrication. Then, in 2013, he purchased the company from its then-retiring founder.

Today, fabrication and machining are located in different parts of the company’s facility, but this is largely because waterjet and welding are such different beasts from small-part lathe and machining center work that they command their own space. Even so, the two parts of the business synergize more than they are separate, and this is seen most clearly during a walk through the CNC machining part of the shop. Seemingly at every machine tool, the jobs that are in work include accumulations of shiny, repetitive parts being arranged in order to complete a shipment to a customer, along with weldments in sets of just one or two requiring machining in order to be completed.

Mr. Carr explains that those weldments make their way through the CNC area because practically every fabrication job is ultimately a machining job as well. A weldment frequently needs precision machining for critical features such as mating surfaces. Indeed, this speaks to the particular level of skill required of the company’s machining personnel. A weldment clamped for machining is liable to warp back to its inherent shape upon unclamping, violating tolerances. Engineered Fabrication’s machinists therefore know how to use shims effectively to clamp a weldment in its free state so that it can be secured for machining without distortion. Because of the need for this kind of skill, the company has always needed machining capability of its own. Expanding into job-shop machining was a way to (A) make use of this capability when it wasn’t needed for weldments and (B) expand the range of services the company could offer to its current customers, many of whom were looking not just for fabrications, but also for a trusted supplier to whom they could outsource some of their piece-machining work.

Still, having the two capabilities in the same company does mean having essentially two different cultures under the same roof, because the two different groups of skilled team members come with somewhat different needs. Perhaps the most basic detail in which the difference has expressed itself relates to the number of hours per day an employee should work.

Four Tens?

Mr. Carr spent much of his career in CNC machining before coming to this company. Partly because of this, he is generally a believer in employee work weeks in which each team member works four 10-hour days. And this work-week structure is popular among employees (some of them), because it gives them longer weekends. From Mr. Carr’s perspective, the chance to stagger employees’ patterns of working four days (so that each employee alternates between a two-day weekend and a four-day weekend) lets him keep the shop staffed through 50 hours per week without this staffing incurring overtime. In pursuit of all of these preferences—his own and some of the employees’—he once tried to move the entire shop to this timing.

And doing so was mistake, he says.

It was a mistake, he came to realize, because it did not suit fabrication employees as well as it suits machining employees. In retrospect, the reason why is not hard to see, given the difference in their work. On a machine tool—particularly a CNC machine tool, but even on the shop’s large boring mill—the machine itself does the work. The employee oversees the work, inspects it and is in motion in large part to prepare for the next job. By contrast, in fabrication, much of the work is welding. This is more active and demanding work that can become tiring if the day stretches from eight hours to 10.

“You have to take care of your people,” Mr. Carr stresses. There was a lesson to be learned in this experience, and he learned it. The company reverted to a more typical workday and stuck with it for a time. Now, more recently, Mr. Carr has decided to go further in acknowledging that there are real and significant differences between these two different teams. The shop is shifting to a more complex plan in which the machine shop does work four 10s, while the fabrication shop continues to work five 8s.

Lindsey Carr faced and appreciated the differences between the two teams when she worked to install and transition the shop’s procedures to ERP. In this effort, however, the production floor in either group was not the biggest area of challenge. Given where Engineered Fabrication was at that time, the challenge with implementing ERP was in the office, not in the shop, because of the need to transition from an office process that wasn’t then computerized. On the floor, the employees generally recognized the benefits that would come from better management of the shop’s data and better tracking of the shop’s work. They acclimated to the new steps that ERP required. Yet one difference she did note between fabrication and machining is that the machining team seemed to become more quickly established at policing itself about clocking in accurately for different jobs. That is, members of this group were quick to step forward to admit when they had forgotten to clock into a job, meaning the record would need to be manually corrected. That self-policing helped them, because data for one job would be used to establish the reference by which another job was planned. Too few hours clocked for a given run of parts could result in far too little time allotted for another job like it.

A bigger difference came when Ms. Carr engaged on the ISO 9001 efforts. The documentation requirements of this certification had the effect of pushing even more accountability, and even more policing, to the shop floor. ISO created the need for a sign-off on the shop floor at the point of the job being completed. In fabrication, this raised an obvious and significant question: Who would do the signing?

The act of placing a signature includes a certain commitment, she notes. Inherent to the signing is a judgment about the completeness and quality of the work, potentially including a judgment about others’ contributions to that work.

“Just a signature changes things,” she says.

Everyone Accountable

Here as well, it was the differences in the natures of the work that produced the difference in the response to this requirement. A machinist making one piece after another is essentially working alone, and this person is already, in a sense, signing off. Frequently, every piece in a machining run is gaged, and in each case, all of the measured dimensions either do or do not conform to specification.

Custom fabrication is different from this. Rather than a single moment of gaging, the structure being produced might undergo many modifications and controls throughout its construction, aimed at making it effective for the ultimate purpose it will serve. And rather than one person working on many pieces, frequently it is many people working on the same big part. Given all of this, is it fair to have one person sign off, declaring his accountability for the efforts of the others and declaring himself as the one to approve what they have done? Particularly when the quality requirements often are not as precisely defined as they are for a machined workpiece?

To the Carrs, the reasonable answer seemed to be: No, quite likely this isn’t fair. The result is another instance of different procedures for different parts of the shop. In fabrication, it is an allowance and a requirement of the ISO procedures the shop authored for itself that all the employees involved in a fabrication project sign off on the job. Essentially, they decide together that the work is complete.

A pending change to the shop’s ISO procedures will also affect the fabrication area, Mr. Carr says, giving these team members even more autonomy. One inefficiency he believes he has observed in the shop’s procedures as they now stand relates to changing the sequence of operations performed on a given fabrication job. Such a change is commonplace; certain welds and certain subcomponent machining could be done in any order, so the fabrication team looks for opportunities to seize on open stations to advance the job through the shop more quickly. Right now, however, this involves rewriting the router, a time-consuming step. In a future version of the ISO procedures, fabrication employees might be more free to change sequencing without this rewriting, a freedom the machining employees generally do not need.

ISO provides a framework to build on in this way, says Mr. Carr. Defining the process is the first step to seeing where to improve the process, and where added flexibility might lead to nimbleness rather than uncertainty, efficiency rather than waste.

And procedural differences such as the one being contemplated, far from separating the different teams from one another, actually help to tie the organization together. Different people in this company might have different skills and roles, but one detailed set of ISO procedures defines how they all fit in and how they all work together. Thanks to these procedures, ideally there is nothing to adjudicate between the two groups, and no room for personality differences or differences in the culture to tip the process one way or another. There are no judgement calls that need to be made, because the ISO effort has forced everyone to think through the important questions in advance.

“The end goal of all of this, and the real benefit of ISO certification, is a process that runs smoothly on its own because everyone agrees how it should run,” Mr. Carr says. That is, the benefit is a process that doesn’t absolutely require him—or Ms. Carr, or anyone else who might be in an oversight role. The team members on the shop floor, in both areas of the shop, already have the skill, talent and desire to do the work well. ISO just provides the structure. “If we do this right,” he says, “then the process should perform the same way, every day, whether anyone is here to lead it or not.”

Related Content

How this Job Shop Grew Capacity Without Expanding Footprint

This shop relies on digital solutions to grow their manufacturing business. With this approach, W.A. Pfeiffer has achieved seamless end-to-end connectivity, shorter lead times and increased throughput.

Read More5 Tips for Running a Profitable Aerospace Shop

Aerospace machining is a demanding and competitive sector of manufacturing, but this shop demonstrates five ways to find aerospace success.

Read MoreERP Provides Smooth Pathway to Data Security

With the CMMC data security standards looming, machine shops serving the defense industry can turn to ERP to keep business moving.

Read MoreWhen Handing Down the Family Machine Shop is as Complex as a Swiss-Turned Part

The transition into Swiss-type machining at Deking Screw Products required more than just a shift in production operations. It required a new mindset and a new way of running the family-owned business. Hardest of all, it required that one generation let go, and allow a new one to step in.

Read MoreRead Next

3 Mistakes That Cause CNC Programs to Fail

Despite enhancements to manufacturing technology, there are still issues today that can cause programs to fail. These failures can cause lost time, scrapped parts, damaged machines and even injured operators.

Read MoreThe Cut Scene: The Finer Details of Large-Format Machining

Small details and features can have an outsized impact on large parts, such as Barbco’s collapsible utility drill head.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)

.png;maxWidth=300;quality=90)

.png;maxWidth=300;quality=90)