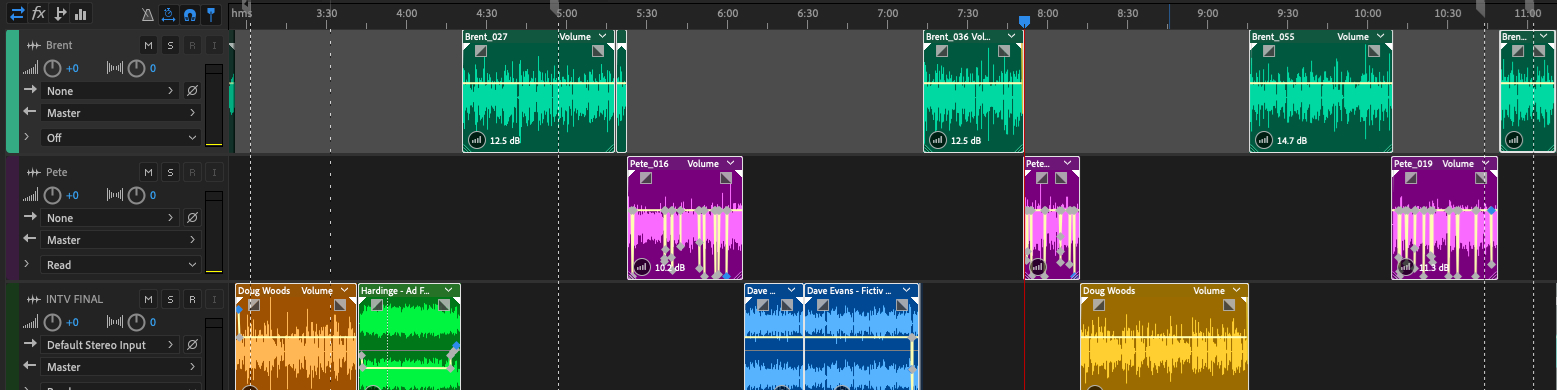

The following is a complete transcript for Episode 3 of the “Made in the USA” podcast. In addition to the hosts, the commentary in this episode is provided by:

Randy Altschuler, CEO, Xometry

Dave Evans, CEO, Fictiv

Heidi Hostetter, Vice President, Fauston Tool & CEO/Founder, H2 Manufacturing Solutions

Susan Houseman, Vice-President and Director of Research at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research

Rick Kline, Jr., President, Gardner Business Media

Doug Woods, President, The Association for Manufacturing Technology (AMT)

Listen to Episode 3 here, or visit your favorite podcast platform to subscribe to “Made in the USA.”

Brent Donaldson: Welcome to Made in the USA, a podcast that dives deep into big-picture topics facing American machine shops and manufacturing large. I’m Brent Donaldson.

Pete Zelinski: I’m Pete Zelinski.

Brent: So to do that, to talk about the most important ideas in manufacturing, we have to talk about a term we heard a lot in 2020… a term that suddenly was on the radar for most of the country during the spring of 2020: the supply chain.

Pete: The supply chain. We saw shortages and delays with so many products during the course of 2020. All of us encountered empty supermarket shelves for certain types of products, long shipping delays for certain items on amazon; I even noticed some retailers spacing their merchandise out more widely to make it better cover the shelf space in the store.

Brent: More crucial was the impact on the medical sector and specifically on health care first responders. Things like gowns and N95 masks were in dangerously short supply. Ventilators couldn’t be made fast enough. Most of us never have to think about supply chains for the common items we buy and use on a daily basis… but then… suddenly those supply chains were seen to bind and limit whether we can access items when we want or need them.

Pete: Supply chains were even the way we first experienced COVID-19 in the United States. Those of us writing about manufacturing were reporting on this. Before the health crisis in the U.S., before any of the lockdowns, first manufacturing was affected. The shutdowns in China meant U.S. manufacturers could not get the components they needed to produce. China’s shutdown was leading to stoppages here. The supply chain was pulling tight.

Brent: So what lessons, if any, did 2020 teach, and what should we know about our manufacturing supply chain?

Pete: To get started, first, let’s just explore: what is the supply chain? Is it really a chain? What does it supply?

Brent: To answer, let’s turn to a voice we first heard in Episode 1. This is Doug Woods, president of AMT, The Association for Manufacturing Technology.

Doug Woods, President, The Association for Manufacturing Technology (AMT) Photo Credit: AMT

Doug Woods: Maybe people just kind of just throw it out there as a term. But if you think about, there's not much you can make where you do everything yourself. So you need, if you're, going into our industry, so if you're making a robot, or you're making a machine tool, I mean, you need cast components, you need electronic components, you need wire ways, you need a controller, you need capacitors, you need end effectors, you need seals. So there's lots of things that you need, and those things have to come from lots of different people. And again, what we did over decades, when we outsource the main part of the manufacturing, the supply chain went with it.

Brent: The “chain” is an image, and we shouldn’t take that image too literally. The supply chain is in one sense a chain, because in some cases, one step has to follow another step… one part or component is needed to produce a larger part, or component, or subassembly. Which means that if any link in that chain breaks, then all the links connected to it are lost too.

But in another sense, you can think of the supply chain as various, different chains in parallel, that all come together later. In fact, an entirely different image that also fits is not a chain at all, but more of a river… the way lots of tributary streams flow together at different points to form a single, larger, stronger river at some point downstream. This is a good analogy when production of a product keeps flowing consistently and uninterrupted…. All of the various suppliers producing different subcomponents —the parts, castings, wires, electronics that Doug woods mentioned… they are all tributaries to that river. But 2020 saw lots of those tributaries get dammed up.

Pete: Supply chains are here to stay. The manufactured products we rely on are too complicated for the companies that invent, design and sell those products to also be effective at making every single aspect of those products. That is just too many things to be expert in. For every separate component of a system, there are manufacturers that have learned to be specialists in making that item effectively. The question, really, is how those supply chains will be organized, and how far they will stretch. According to Dave Evans, CEO of the manufacturing broker Fictiv, a company that puts manufacturers and manufacturing buyers together all over the world, there are basic tradeoffs here.

Dave Evans, CEO, Fictiv. Photo Credit: Fictiv

Dave Evans: I think any supply chain order engineers thinking about speed quality price, right? That's our three legs of the stool.

And so quality, we think of as table stakes, you have to have the highest quality product. And then it's always a combination of speed versus price, and how you're pulling these. And so I think, ultimately, like landed cost, whether that overseas or it shipping from Maryland to Detroit, you know, you need to think about the time element of that and the value of that product. And so, my belief is, if you look at the trends that's happened, so take tariffs in 2019, then roll a pandemic with corona on this. And then you know, you can go back a couple years and talk about earthquakes in Japan, you can talk about financial crisis and you can look at, you know, even 911 if we want to go back 20 years, all these things are disruptions in supply chain. I think that two major events back-to-back supply chain orgs are going to come out the other side of this not looking the same.

Brent: Let’s set aside the disruptions for a moment, the black swans that he listed — the big, unusual events that have happened in recent decades. Not to minimize this, because we’ll return to it. But I want to focus on the first part of what he said, which is significant. If you accept quality as a given, if you can get the product that meets your needs from various countries, then the tradeoff becomes speed versus price. On paper, you can see why manufacturing would then go far away. If you know you are going to want a whole lot of a product, and you can sell it for less if you can produce it for less, you may be willing to put up with a longer wait time in order to do so.

Pete: but the problem is, time is cost, also. Taking nothing away from Dave Evans at Fictiv, but the tradeoff is not as clean as that. Time adds costs that are harder to see because you don’t get a bill for them — they are more baked in — and also because some of these costs are paid by all of us. Here is more of Doug Woods; let’s let him start to paint a picture.

Doug Woods: The supply chain wants to be near the thing that it's making. You know, in many cases, they're complicated or they're larger, they're heavy, and you want to integrate in a partner network with your main customer base. And it's difficult to do that if you're 12 hours off and you speak different languages. So, they want to be near. When you bring those pieces back together and have some self-sufficiency, you're building your ability to iterate quickly, your ability to have kind of micro-manufacturing instead of major manufacturer, you can put in multiple locations to service different areas. Our ability to actually refocus as supply chain for interdependency here, can really drive our manufacturing to the next level.

Brent: He said “micromanufacturing” versus major scale manufacturing. How much of something do I need to make? The farther away the supply chain stretches, the more I have to produce. And that is a cost. To understand this, it might help to think about the cost of inventory. A warehouse full of products waiting to be sold is inventory, and the manufacturer has to pay for that. The manufacturer is paying rent on that building, for one thing. But more than that, all of the product sitting on shelves represents money that’s tied up. If the company could sell all of it at once, there would be enough money for another piece of equipment or another factory to produce even more product. Well, when the supply chain is long, there is a lot of inventory. There are some components waiting on shelves because a shipment of parts that connect to them hasn’t arrived from another supplier. All of the products stored on container ships that travel across the sea, or sometimes famously get stuck in the Suez Canal, that’s inventory, too.

Pete: And then, what if something changes? Doug Woods mentioned iterating quickly. What the market wants or needs can change, and if the supply chain is shorter, because it’s closer, then the manufacturing can adapt more quickly. I know a case of a us manufacturer that ramped up production of a construction-related tool that would help with meeting a new building regulation. The regulation got repealed while a huge production run of this tool was in work, in china. The company is stuck with a whole lot of this tool it still hasn’t been able to sell. Suffering with problems like that is a cost as well.

Brent: I believe you also mentioned societal costs, the costs we all pay for. Our friend Susan Houseman has something to say about that. We met Dr. Houseman in Episode 1; she is vice-president and director of research at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. As she describes, the problem with relocating supply chains is that a lot more of us work for those supply chains than we realize.

Susan Houseman, Vice-President and Director of Research at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. Photo Credit: Upjohn Institute.

Susan Houseman: Well within the manufacturing sector it has very deep supply chains, and a rule of thumb if you look at you know data that the U.S. government maintains and you see similar patterns in other advanced economies is that, roughly half the jobs I used that are involved in producing manufacturing goods are counted outside of the manufacturing sector. So, it could be more than more or less in, depending on the industry, how things are structured, how automated the manufacturing processes and how much they outsource stuff like you know, logistics and transportation and repair and all kinds of things.

So, really just inside manufacturing alone, let's say we account accounts today for a little under 10% of employment in the country. If just as a rule of thumb, we double that, or maybe a little more than double that, in terms of people whose jobs are directly connected to manufacturing, you're getting up to something more like one and five. So, you know, plants that… more than 20% of factories in this country closed in the in the 2000s. Those have large adverse effects on local economies. You know, people who lose their jobs don't buy as much. They cut back on eating out at restaurants going to movie theaters and so forth, other sorts of purchases. And so, you just see a spill over. And it can have quite devastating and lasting effects on certain parts of the country. And i think that's what we saw.

Brent: Truck drivers, repair technicians — we don’t categorize them as manufacturing, but they are part of the supply chain. Their work doesn’t exist, or doesn’t exist nearly as much, without the manufacturing supply chain. And then, in certain parts of country where manufacturing used to be stronger than it is today, we discovered that restaurant owners and other service workers are part of the supply chain, too.

Pete: It asks a lot for the manufacturing company to consider all this. In fact, it asks too much. That company has to stay in business; it has to make decisions that result in it being as profitable as possible. But someone has to think about these costs. Manufacturing companies need to remain profitable within a context structured to make sure all the costs are considered.

Brent: Ok, societal costs. Let’s talk about that. I would say that in 2020, many of us, perhaps most of us, learned a least a little bit about how much we rely on the supply chain — how much we are affected by it. Somehow, we should have had more medical personal protective equipment on hand, or a more reliable source of supply. We have to figure that out. And these are problems manufacturers should want to fix, too because they were directly affected. They had customers and markets they couldn’t serve because they couldn’t obtain product.

Doug Woods: Let's see how the supply chain issue, I mean, really, it's been brought into a high degree of focus now because of Covid. But the reality is we had a really good taste of it with the tsunami in Japan with a lot of the components and things we get out of Japan and Asia and the impact there. We had a good taste of it at 9-11, when you shut down basically air travel everywhere and had to rethink how things are deployed and shipped. So, we've had some early warning signs that it's problematic. But really, up until this we haven't had kind of a global perspective as well as a national perspective or even a nationalistic perspective, of the absolute dire necessity to make the change.

So it's driving not just the U.S. to look at it. I mean, even China, where everyone's talking of course about all the things that… You know, China, there's lots of geopolitical issues over China. But I mean even and people have not sent their manufacturing to China because China's figured out how to scale manufacturing dramatically to supply people's needs. Even they are thinking about, they in China have outsourced their manufacturing to Vietnam and Malaysia and UAE, because the concept of chasing the lowest cost dollar of manufacturing is a short lived solution. It makes no sense at all. I've been talking about this and as long as I’ve been in this job, and it's kind of crazy, you know, this concept of, you know, what we're going to keep going with the cheapest dollar is. And at some point, what's happened is, what happened in China is the dollar or the cost, the wages just keep going up. Because as you get more and more people employed, and the supply chain goes there and hires more of the people and you can't get certain things, and then they want to get apartments and buy things, costs go up and up and up.

So, when you see China doing the same thing, outsourcing, the light bulb should go off for people going… Look, we can't keep chasing the low-cost country until we've gone through everybody in the alphabet all the way down to Zimbabwe for the lowest cost wage, because the same thing will eventually happen. You need to focus on your core capability within your own area.

Dave Evans: You can go back a couple years and talk about earthquakes in Japan, you can talk about financial crisis and you can look at, you know, even 9-11 if we want to go back 20 years — all these things are disruptions in supply chain. I think that two major events back-to-back, supply chain orgs are going to come out the other side of this not looking the same.

If I’m a supply chain leader, I am not going to do the same type of business that I did in 2019. I think the concept of reshoring or going back to the U.S. or going out of low-cost areas, I believe that supply chain leaders will look for more agility in their solutions.

Brent: In fact, one of the positive lessons of the COVID-19 crisis is the discovery that, to some extent, the needed capacity was ready and waiting. Here with a perspective on this is voice that all of my coworkers should recognize. Our boss:

Rick Kline: Hello, I'm Rick Klein, the president of Gardner Business Media.

Pete: Gardner Business Media is a fourth-generation, family-owned company producing magazines, like Modern Machine Shop, websites, conferences and other information sources focused on manufacturing. Rick points to the way U.S. manufacturers rose to the sudden and unexpected need.

Rick Kline Jr., President, Gardner Business Media. Photo Credit: Gardner Business Media.

Rick Kline: We have very clever people that are involved in manufacturing in the U.S., a lot of these companies that filled the void, whether it was for ventilator parts or for equipment, a lot of these companies were small- and medium-sized companies that are often ignored by our government and ignored by the media in terms of the importance that they play in the supply chain in the U.S., and how flexible, creative, and really patriotic, a lot of these people are that want to step up when there's a need, our manufacturing community in the us will find a way to meet that need.

So, ventilators are probably the most well documented and at the time were the most critical item that that we seem to have a supply problem with and when you look back at that point in time, companies that never were involved in medical manufacturing, they might have been supplying parts for the automotive industry or for other parts of our economy. Having a government-directed plan to try to meet these needs would have been not nearly as effective and not nearly as efficient as the way things did happen to meet those needs.

Pete: So, can we lean into, make greater use of, these domestic sources of supply? Let’s introduce another voice. The company Xometry is a type of manufacturing service provider the digital economy makes possible, acting as an interface and facilitator to accept manufacturing jobs and convey the work to manufacturers with open capacity. I referred to Fictiv earlier as a manufacturing broker. The word describes Xometry, too, which plays a similar role. In a way, these companies have a front-row seat to change in the way manufacturing buyers are thinking about supply.

Randy Altschuler, CEO, Xometry. Photo Credit: Xometry

Randy Altschuler: I'm Randy Altschuler, I'm CEO of Xometry. Xometry is an online platform that connects thousands of customers and suppliers of custom manufactured parts.

Yes, I mean even like yesterday there was a $50,000 order, and the customer said you know, we've done this in China. But everything we've got there right now is simply too far backed up. What was it a work shortage? We don't have the competence for it. I need to get this piece immediately. I need to do it right away.

And we've been seeing that you know, since the outbreak in China, we've definitely been seeing… So xometry itself has as part of our, we have a China option for customers, and so as the China thing unfolded, and there were delays, we went back to our customers who ordered from us to China, we went back and said, hey, we've got a whole domestic network. Are you interested in switching back to the United States? And we had a bunch of customers who did that. So I think that trend will accelerate or, or people will redo their models, and it won't just be about cost.

I think even we've heard even the people who didn't ship jobs back to the U.S., they have asked for pricing in different places, right. So even if they have not yet made a decision about whether to do it, they're creating their different options so that they can do one or the other. You know, how much time is it going to take to get from china? What's it going to cost here?

Yeah, I think absolutely, Brent. Look, I think there's a recognition for the security of the United States and for the health of our economy, we need to have the capabilities domestically as well, because it's become clear from this from this terrible event that entire continents are potentially getting shut down. You know, because of the virus. And American people still have to live their lives and have important goods, so have our supply chain shuts down because 20% of it can only be sourced and another continent. That's simply not acceptable.

So , I think after all is said and done, there's going to be some reflection and understanding that we have to have redundancy. At the very least, we have to have those capabilities within the United States and people need to start bringing back some of this work.

Brent: Ok, stick with me here! Randy said, “redundancy,” and in a way that brings us full circle. Redundancy in the supply chain is an insurance policy. It is extra capacity, in parallel, so if one river of production is shut down for some reason, there is another one that can let the company obtain at least some of the production it needs. The cost of a supply chain stretching long distances is inventory — all the product that has to be stored at any one time, or all the product that is either in production or already on ships. The cost of redundancy is extra capacity.

Is this a better cost? The answer is yes, because if the redundant capacity is close to home, then it can be redeployed more quickly. This is capacity that is adaptable to shocks and changes, rather than being vulnerable to them.

Pete: I was talking to an emergency room doctor during the spring of 2020. He was in the pacific northwest, where hospitals had just been nearly overwhelmed with covid-19 cases. They faced looming shortages of masks and gowns, and other hospital supplies, just like we were hearing about throughout the year. The doctor said to me, “Do you realize, at any given time, this planet has maybe one day’s supply of medical PPE? That’s it. Take that and we have to make more.” All of us who work in manufacturing or report on manufacturing know what he is referring to. The inventory costs in the supply chain — those are huge costs. And manufacturers work to control them by producing as close to demand as possible, producing “just in time,” as the phrase goes. The incentive in supply chains, near or far, is always going to lead them to produce this way. But that means distant global supply chains can’t help us in a crisis. We need capacity close that we can shift, amp up, or redeploy when the crisis comes.

Randy Altschuler: Yeah, so I think there are a couple trends. One is, I think the future is more distributed manufacturing. So, the internet and now to see companies like Xometry and others enable U.S. companies to tap into manufacturers all across the country. And in the past, that ability just wasn't available to customers. They just didn't know that there was a great machine shop in North Dakota, or in Utah if they were located in, you know, the northeast. And the internet and companies like Xometry provide that visibility and transparency that will become more popular As ability to tap into the skills but also to mitigate risks, supply chain risks, that arise in these kinds of situations.

So I think distributed manufacturing will become more popular. That will also put more of a focus on smaller manufacturers because you won't need somebody who can make a million of something. You need somebody who can chunk out 10,000 or something. With 5,000. That's also where we, where the U.S., plays really well versus offshore.

Pete: So, we need the supply chain to come back, to not stretch quite as far. Or, at least, there is real benefit to it getting shorter, for the supply chain to be largely within the USA for products that are wanted and needed in the USA. If you see manufacturing demand and manufactured products as something fixed, never changing, then maybe it makes sense to do the production wherever the direct costs are the lowest, relocate manufacturing there. But manufacturing changes; it is dynamic. As we saw in 2020, huge developments can bring very serious immediate changes to the kind of manufacturing needed, and changes to the access to manufacturers. Supply chains that are close can respond to things like this. Supply chains also bring real benefit, because a lot of good work, sources of livelihood, are potentially part of that chain. And as we’ve seen, there are some clues that some of this kind of thinking about supply chains is already starting to occur.

Brent: We are all in this together. The supply chain connects different companies and connects many different people into mutually beneficial links that we can all hold onto together. What about a day when much more of the supply chain is domestic? Can we think about it as a shared resource in this way; can the different actors, the different companies, see the supply chain this way? Let’s wrap this up by hearing from a manufacturer. Here is Heidi Hostetter, founder of H2 manufacturing solutions and vice president of Fauston tool, mid-sized contract manufacturer that produces aircraft and defense parts from their machining facility near Denver, Colorado.

Heidi Hostetter, right, Vice President, Fauston Tool & CEO/Founder, H2 Manufacturing Solutions. Photo Credit: Brent Donaldson

Heidi Hostetter: So one of the things that I've noticed is that, and I will only use our local corporations as example, but you have these big corporations. Let's pick on Woodward, okay, for example. One of the biggest employers in Colorado, and they're a global company. What we know about Woodward, Brent, is that they offload their machining work. So if you look at all the machine commodities on a scale of one to five, one being a bracket and five being a high end, like, let's say a, some sort of gas valve or something for a jet is a five — super complex, lots of dimensions. At about the two-and-a-half mark, what we know is that they're going to offload it for whatever reason… liability… who knows who knows what. Their overhead is more than mine. Okay? So, they're going to offload that part to me. And I'm going to take anything from a two and a half up to a five for the Balls and the Woodwards of the world, okay, the Lockheed Martins. We actually know that data. And my guess is, that's the case around the nation, if you if you really scrub that. So here's what I'd say: Why are we all competing for the same person? In other words, we're all aerospace. Lockheed Martin, you take the guy, you take the guy out of the community college, the apprentice, the intern, whatever you want to call it, and you work with them up to the two and a half level, and then transition them out to me. Because otherwise we're just competing for the same people. And we're pulling the same people out of the same programs and they're, you know, not ready and it ends up just being this complete cluster.

So I'd like to see that whole thing revamped as far as how we work with the apprenticeships. The big corporation into the smaller supply chain guys, because most of the supply chain is made up — 80% of it — is made up of small business, small manufacturing.

Brent: It’s hard to forget just how surprising it was at the onset of the pandemic when many household items that many of us take for granted were suddenly no longer available in stores and supermarkets. And I’m not even talking about masks and disinfectant, but tissue paper, and baking yeast, and fitness equipment and gaming devices. The pandemic disrupted supply chains around the world, and, remember for the U.S., this happened on the heels of when tariffs were impacting American companies that were manufacturing in China.

I remember reading a survey of supply chain professionals stating that COVID-19 disrupted nearly 80 percent of supply chains around the world — a bigger disruption than any event in the last decade.

So if the end result is that, collectively, our society has a greater awareness of how supply chains work and the pitfalls that exist when you don’t prepare for disruptions, I think we can chalk that up as an important lesson learned.

Pete: You mentioned earlier, the supply chain is just an image. It’s just an analogy. It’s true as far as it goes, but it’s worth focusing on who those suppliers are who are in the supply chain. Every company at every stage of production of a complex product is a specialist in some form of manufacturing. They know how to do their specialty very well, whether it’s machining or plating or joining or wiring or painting or assembly. There is a lot of skill, a lot of technology, a lot of value added at each step. Each of these steps is not just a link in a chain. And we minimize each of those steps, each of those processes and operations if we carry that analogy too far. So in a sense, no step in a supply chain is just a link in a chain.

But then, think about how far the supply chain really goes. And what it does. A company making a car is selling it to a person who is going to work in a food company. And the food that that company makes is among the groceries of someone who works in a doctor’s office. And that doctor’s office helps take car of the person working in the car company. So in one sense, no one is simply a link in a chain, but in another sense, we are all part of the supply chain. We are part of many chains, many different, intersecting, crisscrossing supply chains, and they connect all of us. So these questions we’ve been exploring, these questions about the supply chain, they’re important. If the supply chain stretches too far, all of us feel the pull.

Brent: Made in the USA is a production of Modern Machine Shop and published by Gardner Business Media. This episode was written and produced by Peter Zelinski and by me. I also edit the show.

Made in the USA was recorded at the historic Herzog Studio, home of the non-profit Cincinnati USA Music Heritage Foundation. Our outro theme song is “Back Home” by The Hiders.

If you enjoyed this episode, please, go tap that fifth star in the Apple Podcasts review. It’s super helpful and allows people to find it more easily.

If you have comments or questions, email us at madeintheusa@gardnerweb.com. Or check us out at mmsonline.com/madeintheusapodcast.

For our next episode, we’re going to get into “perception vs. reality” when it comes to modern American machine shops and manufacturing careers. We all know that our beliefs shape our world every bit as much as actual facts. That’s a challenge for U.S. manufacturing when Americans believe that employment in manufacturing is something different than it actually is. Manufacturing perception versus reality, next time on Made in the USA.

Read Next

3 Mistakes That Cause CNC Programs to Fail

Despite enhancements to manufacturing technology, there are still issues today that can cause programs to fail. These failures can cause lost time, scrapped parts, damaged machines and even injured operators.

Read MoreThe Cut Scene: The Finer Details of Large-Format Machining

Small details and features can have an outsized impact on large parts, such as Barbco’s collapsible utility drill head.

Read More