How Scalable is Machining?

Tiny tools don’t behave like big tools do. One researcher explains why.

Share

Shop-floor arithmetic is enough to reveal why the smallest cutting tools are not yet able to achieve the same relative performance that full-size cutting tools achieve. Part of the obstacle is spindle technology. For a 0.002-inch-diameter cutting tool to achieve a cutting speed of 100 sfm, the spindle speed would have to be nearly 200,000 rpm. If the diameter is smaller or the cutting speed is higher, then even higher spindle speed would be needed. Few machining centers offer even the option of using a spindle this fast. In fact, machining spindle speeds far in excess of 200,000 rpm have been achieved only in research settings.

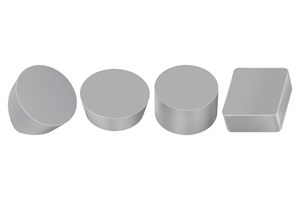

Then there is runout. For full-size machining, keeping total tool runout to no more than 10 percent of tool diameter can be a generous standard. But applying even this loose standard to something like the 0.0004-inch cutting tool shown in the photo would produce a maximum acceptable total runout of only 1 micron. Alternatively, tool runout is sometimes held to 10 percent of chip thickness. If a micro-size milling tool much larger than the one shown took a chip thickness of 0.0002 inch, the corresponding runout would be 0.5 micron. Considering the potential stackup of error for the spindle, toolholding device and tool, holding total runout to this range—1 micron or 0.5 micron—is impractical at best.

Among the organizations attempting to work past these sorts of limitations are various micromachining-focused institutions and small businesses sharing space within “Eigerlab,” a manufacturing business incubator in Rockford, Illinois. Northern Illinois University has micromachining researchers who work at this facility, and the company building the machine tool described in the article under "Editor Picks" at right is also headquartered here. So is micromachining researcher Kanwar Singh of Rockford Engineering Associates.

Mr. Singh says the limitations described above—spindle speed too low for the tool diameter, plus relatively high runout—are two realities that currently have to be accepted in micromachining.

There are other realities like this, he says, one of which relates to the quality and consistency of the material.

Hitting A Stone

Mr. Singh says a full-size cutting tool—a tool measuring 1/2 inch or even 1/4 inch in diameter—is so big compared to the microscopic variations in the material of the workpiece that it could be likened to a shovel. Each cutting edge scoops out a chip that contains hard spots and soft spots, just as a shovel picks up both small stones and dirt. The net hardness throughout each chip tends to balance out, and the load on the tool is steady.

However, with smaller chips that are closer to the size of inclusions in the material, the potential for variation from cut to cut increases. A cutting edge might pass from harder metal into a soft inclusion, resulting in a shock that might affect the life of the tool.

Predictable tool life in micromachining therefore requires high-quality workpiece material. Inconsistencies introduce perils when the chip thickness is small. Indeed, Mr. Singh says a different peril of small chip thickness illustrates why keeping the chip sufficiently large is an important requirement of micromachining.

Smear Tactics

It might be counterintuitive to think that a cutting tool so delicate that it could be bent with the pressure of a finger might not perform well unless the chip thickness is relatively large. However, the minimum chip thickness requirement is one case where the micro-size cutting tool actually does perform the same way as a full-size tool.

The reason for the requirement relates to the cutting edge radius. In full-size machining, shops know all too well how the cut behaves when the edge radius is large relative to the cut, because machining with a worn tool provides an example. When tool wear increases the edge radius, the sound of the cut changes and the finish of the workpiece degrades. The dull tool has ceased to shear the material and now plows or smears the material instead.

A very small tool is subject to this same effect even when the tool is “sharp.” That is because the small tool’s edge radius is large compared to its diameter. Too light a chip thickness produces a cut that is too small for the edge to be “sharp” relative to this chip, so the material is removed through smearing rather than shearing.

But maintaining this minimum thickness is difficult in milling. When the tool path changes direction—which it frequently does in milling—the feed rate slows. But the spindle rotates at a fixed speed as the feed rate decreases. Therefore, the chip thickness shrinks and ultimately enters the smearing range.

This can’t be avoided in milling because constant feed can’t be assured. However, Mr. Singh says the effect can be controlled to such an extent that its impact on the process is small. Testing has shown that optimal tool life can still be maintained as long as the minimum chip thickness is not lost for more than two spindle revolutions during acceleration and deceleration.

Obviously, this isn’t much time. The machine needs to make the direction change this quickly. The faster the spindle runs, the more quickly acceleration and deceleration need to occur. A 0.010-inch tool run at 180,000 rpm would need 5G acceleration, he says. This is much more acceleration than a typical machine tool is likely to deliver.

This condition, then, points out one more performance limitation that affects micromachining. That is, machine tools do not accelerate fast enough to take advantage of all the spindle speed that tools could use. Given this lack of acceleration, a spindle that is fast enough for the tool would likely destroy the tool—contributing to tool failure by keeping chip thickness too small for too much of the cut.

Thus, in a way, it’s good that spindle speed is limited. So long as the acceleration is constrained, spindle speed should be constrained too. Settling for a spindle speed that is low for the size of the tool means the two-revolution window lasts longer—making it possible to effectively use machine tools having acceleration rates that fall short of the 5G mentioned above.

What This Means

None of this means that micromachining cannot be performed effectively. It can. Machines with higher spindle speed, acceleration, stability and precision can make effective use of tiny tools.

What it does mean, Mr. Singh says, is that relative performance—or micromachining that behaves just like full-scale machining scaled down—cannot currently be achieved.

As a result, micromachining is something fundamentally different from conventional-size machining. Somewhere between full-scale cutting tools and the tiniest cutting tools, there lies a threshold beyond which the expectations for

what constitutes acceptable machining performance have to change. The procedures for realizing that different level of acceptable performance have to be relearned for this realm. In fact, they have to be learned through trial and error within every different process or application that attempts to make use of micromachining.

Related Content

Ceratizit Product Update Enhances Cutting Tool Solutions

The company has updated its MaxiMill 273-08 face mill, WPC – Change Drill, as well as the HyPower Rough and HyPower Access 4.5-degree hydraulic chucks.

Read MoreEmuge-Franken Threading Tools Mill Challenging Materials

The company has expanded its offerings of solid-carbide thread mills with new products for challenging applications.

Read MoreWalter Ceramic Inserts Enable Efficient Turning, Milling

Suitable turning and milling applications of the WIS30 ceramic grade include roughing, semi-finishing and finishing, as well as interrupted cuts.

Read MoreRead Next

OEM Tour Video: Lean Manufacturing for Measurement and Metrology

How can a facility that requires manual work for some long-standing parts be made more efficient? Join us as we look inside The L. S. Starrett Company’s headquarters in Athol, Massachusetts, and see how this long-established OEM is updating its processes.

Read More