Listen to the third episode of season two here, or visit your favorite podcast platform to subscribe to “Made in the USA.”

Catch up on season 1 here.

The following is a complete transcript for season 2 episode 3 of the “Made in the USA” podcast.

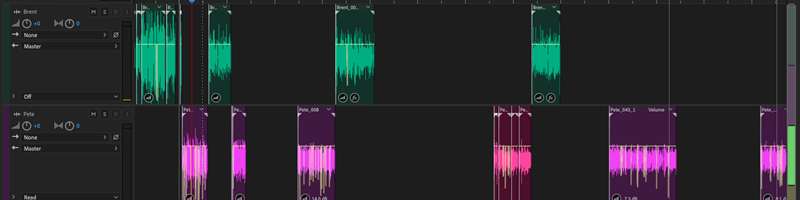

Brent Donaldson, Editor-in-Chief of Modern Machine Shop: Welcome to Made in the USA, the podcast from Modern Machine Shop magazine that explores some of the biggest ideas shaping American manufacturing. I'm Brent Donaldson.

Pete Zelinski, Editorial Director of Modern Machine Shop: I'm Pete Zelinski. In this season of Made in the USA, we're bringing you stories from people making commitments to US manufacturing, people who are making intentional choices to keep manufacturing in or bring it back to the United States. So far, we've heard from people whose motivations range from what we might call economic patriotism, to supply chain concerns, to negative experiences manufacturing in lower cost countries. In this episode, we're bringing you the story of an American robotics company that completely reversed its manufacturing strategy about six or seven years ago, well before the pandemic, from one that relied almost exclusively on Chinese suppliers to a strategy in which nearly 95% of its robots parts are machined, manufactured in the United States.

Brent Donaldson: And not just the United States, but one state in particular, California. The company is Productive Robotics. And one aspect of the story that sort of takes it to another level is that the company's products are collaborative robots or Cobots. One of the key tools helping US machine shops and other manufacturers compete with lower cost countries by automating production. So Pete, let me ask you, what do Close Encounters of the Third Kind, The Grateful Dead, robots and the great downsizing of the photo printing industry have in common?

Pete Zelinski: I bet I could connect to any two of those things, but I can't connect all four so Close Encounters, Grateful Dead, robots declined a photo printing, what do they have in common?

Brent Donaldson: So these are all the concerns of a man named Zac Bogart, who happens to be a Dead fan, as well as the founder and president of Productive Robotics, the Santa Barbara California based company that began selling its line of Cobots in 2017.

Pete Zelinski: In this episode, Zac and Productive Robotics vice president Jake Beahan are going to tell you how and why they went from producing parts 100% in house to offshoring nearly all of it to China to then reshoring nearly all of it back to the US in the span of two decades. But first, in case you're unfamiliar with the term, a cobot is a collaborative robot, a multi axis robot arm and gripper that is meant to work near even next to humans. If you've ever seen large robots working on, say automotive production lines, you'll notice that those robots are all walled off from humans by gates or cages. Why is that? Because they can seriously hurt you if you get too close to them while they're programmed to operate. Cobots, on the other hand, will shut down immediately if they come into contact with a human. They can be stationary or moved around to perform different jobs on a production floor in a machine shop that can be programmed to do everything from picking place to swapping parts or components inside a machine tool to literally closing the machine tool door and pressing the start button.

Brent Donaldson: So here's Zac Bogart.

Zac Bogart, President of Productive Robots and ZBE: I'm Zac, Zac Bogart. Yes, I'm the president of productive robotics as well as ZBE, Inc, which was sort of a predecessor company to Productive Robotics.

Brent Donaldson: And before Zac begins his story, we should point out that the company he just mentioned, ZBE is Zac's first business, ZBE manufactured perhaps the best known professional photo printers known to man, their Chromira line of digital printers and photo processing labs that are still used around the world today. Even today, if you send a photo from your smartphone to be printed by your local CVS or your Walgreens, for example, and you want a size larger than an eight by 10, it's still likely to be printed on a machine made by ZBE. The company still exists, it still manufactures parts, but only for service and part replacement applications. Before ZBE, Zac worked in Hollywood where he learned about a subfield of engineering that would play a role in everything he did later. Motion Control.

Zac Bogart: I started ZBE in 1980 just out of school because it was either that or get a real job. So I started we did motion picture special effects work I was an animation cameraman and specialist had worked in special effects, Motion Picture work. So I started the company to develop equipment, camera systems for special effects. And we developed computer controlled camera systems that were used for shooting space movies and flying scenes and things like that. First two movies I worked on were Close Encounters and Star Wars. I took a year off college. And I was working there, my job was insignificant I was sort of a tech guy. And sort of jack of all trades, building stuff and very little bit of electronics work. But that's kind of where I learned how to do a lot of what I did. And then when I started ZBE, we did tons of commercials, we did a couple of movies, the biggest movie we did was The Right Stuff. We did all the special effects for The Right Stuff And I and my team designed all the special effects camera systems for that. So in those days, these were motion picture cameras shooting on film, with models and giant robots moving the camera around down tracks, down a track flying past models of airplanes with generally some of lighting, some pyrotechnics, that sort of thing. And that's the way it was done. Now it's all computer generated, pretty darn nicely too. But you couldn't do that back in those days. So I developed that equipment. And after a few years of doing that, and continuing in the motion picture business, I basically got kind of bored, and moved on to wanting to develop more equipment. So I rolled a lot of that equipment design into doing special effects still photography work. And then we rolled that into doing more photo lab printing equipment. And that ultimately culminated in our Chromira line of digital large format, digital photo printers, the large format photo Chromira era photo printers are, there are 1000s or hundreds of them, we're not sure somewhere around 1000 of them. And they're running in 60 countries around the world. So they're pretty much the leader in large format, digital photo printing. So we discontinued manufacturing those. Last January was the last one we built, we built them for 20 years, different models. If you order online, any photo print that's bigger than an eight by 10 picture, it comes off one of our printers at one of the large photo processing centers in the US. So if you go to Walmart, or you go to Costco or you go to your local pharmacy, and you order a poster print, that's a photo print, not on Canvas, or that kind of a print, it comes off a Chromira era, premier lab printer that was manufactured in that building. So as time went on, it was pretty clear that the photo industry was declining. And we had sold a lot of printers, but they don't, they don't wear out. And they're continuing to run. And we needed to move on to something else. So we started looking for something else. And what really drove it was I basically asked myself, so we started in Motion Picture special effects with film cameras writing down tracks, and when digital and film went away, and the analog production methods went away, and it was all developed, it was all done on computers. But that ultimately went away, and then we went into doing more work for still photography. And that ultimately went digital as well. And we developed these large format printers, which was probably our biggest success. I mean, they're all over the world. And ultimately, those started going away, why did they start going away because people aren't printing photographs like they used to print them. And if you've walked through an airport in the last 10 years, you'll realize that all those big giant transparencies have now turned into TV sets or large monitors. And we said, what can we do where there will never be fewer of them in the future than there are today? Because everything that we've done and all the development work that we've done, ultimately became superseded by a newer technology, a different technology. And so what can we do that will that our matches our skill sets that we're really good at, and they'll never be fewer of them than there are today. And the answer was pretty obvious: robots. If we didn't know exactly where we wanted to go at first, what we're really good at is making things move and making them move precisely. And controls. That's one thing we're really good at. The other thing that we're really good at, is boiling all the complexity out of the users end of, of the operation, and taking out, automating it and taking out anything that looks like programming, anything that requires technical skill to pull off. So at first, what we did was, we did a lot of research, like hundreds and hundreds of research papers for like, a couple of months, trying to figure out where we needed to go, what we could do that was going to be different, where the technology was going, what could we do in developing a robot that was going to make it so anybody and everybody could use it without any background without any training without any programming, and would actually do real work. And so that's what drove us to the robots that we're doing today.

Pete Zelinski: Here's Jake Beahan, Productive Robotics vice president who started working with Zac as an intern at ZBE back in 1999. As Jake explains, Productive Robotics technically began in 2010, but only very slowly as a secondary company to ZBE, which was still producing machines and maintaining its core engineering team. As it turned out, one of the reasons that Productive Robotics focused on machine shops as a target market is because of ZBE's own experience with offshoring production, when demand began to outpace its shop's capacity. Until that happened. ZBE was manufacturing 100% of its parts in its own machine shop.

Jake Beahan, Vice President of Productive Robotics: We started with everything. So the entire machine was made here we had about 10 people in the machine shop. At one point. A lot of it was on bridge ports that were converted to be servo driven. We also had a few of the Haas Mills in house and we have a very, very early Haas lathe that's still running here that we made a lot of parts on. But as time has changed, we continually hired machinists, we got really good at training them, and then they would go leave us some work for a machine shop down the road, that was a much bigger job shop that could pay more. And we had a lot of turnover in this area. And that's really truly what led us to outsourcing was unable to hire the people to keep the shop running. And we trained countless people that would come in with no experience in machine shop, we train them how to run the equipment, how to make all the parts, how to measure all the parts, two to three years later they'd all be moving on to a bigger job shop, we got to the point where it's like, how are we going to compete. We were competing by doing it in house. But when we had to outsource it all, we couldn't compete anymore. And we would have had to significantly raise our costs in order to compete.

Brent Donaldson: Here's Zac Bogart.

Zac Bogart: So with the Chromira printers, we had two primary generations of printers, the first generation of printers, all the part, when you say part production, we're referring to CNC machining primarily. All the CNC machining was done here on-site. And in our previous location before we moved here in our shop, and which is what you've seen, it's not very big. When we introduced our second generation, we had somewhere between 300 and 400 CNC parts that had to be produced and to get into production and get into production quickly. And we just, there's no way we could have done it, we just did not have the capacity to prove that many different parts, new designs. So we've always worked with a few machine shops around and we have friends who have machine shops, and we know the machine shops and the whole process and the whole paradigm of running work through US machine shops at the time. The lead times were incredibly long, the pricing was not anywhere near what we could sustain. And particularly, remember we'd been used to building and doing all the machining in house. And the only way that I was going to get this printer in production in two months was to find somebody who could produce initially small volumes of these parts and turn them around quickly.

So at the time, this was 2006 We had a small office in China where we were selling we were the number one selling printer in China at the time and we had a couple of engineers who were doing service and installation and of our printers in China. So through them, we developed a few connections with a few machine shops to start, that we recruited to start making these parts. So literally, we had to turn around, I said three to 400, somewhere in that range, I can't tell you the exact number, I don't remember new parts that had to be CNC machined. In small what is normally considered fairly small quantities 20 to 50s of these parts The very first run, I think we did, we only did 20. And we needed to turn them around quickly and we couldn't find anybody who could do it, never mind at prices that were reasonable or competitive at in those volumes. So we moved all that work directly straight there. And in the process developed some very, very good relationships with a number of suppliers there, again, through our own employees in China. And we did pretty much all the printer CNC manufacturing through two or three key CNC vendors in China. So when we started the robots, we had a whole new thing that we were trying to do here, we had a whole new set of parts that had to be produced, there were fewer of them, the tolerances were higher, which was one of the issues. And we wanted to get the work out of China. For nationalistic reasons, if you want to call it that, but we had a problem because the lead times in US machine shops are long, the pricing structure in US machine shops, historically, has been something that we didn't consider to be effective or workable in the quantities that we work in. So there's sort of three tiers that you would want to work in production that happens that go through CNC, there's the one to 10 part prototype type work that's done. There's the high volume work that's done. That's 1000 parts and more 500 parts and more, okay, we exist in a world that's in small, low quantities of hundreds, and the machine shops that most of the US machine shops, we find there are prototype shops, and then there's some higher volume production shops. But we really couldn't find shops that could do this work in those quantities and do it quickly and efficiently. And cost effectively.

So one of the ways that we approach so the only way that this work gets done cost effectively, and that in the United States that we actually can compete is by automating the work, there's just no other way, the labor rates are simply too high. Now, the labor rates in China are creeping up too. And that's starting to close some of the pricing gap. But we want to bring the work back. It's not just about dollars, okay, it's also about caring that the work is being done in this country and that we're providing the work in this country that matters. But it's also about supply chain, and running a smooth supply chain in the amount of time it takes to get work out of from overseas. Remember this, these parts are big and heavy, and they're not all big, but they're heavy. This is not like shipping an iPad from China, right? This is shipping chunks of metal around the world, Federal Express, it's not cheap. So at this point, the work that we're having done in this country, the CNC work, I think it's all out of China, there might be a few little parts that are left, but the parts that are still left that we're doing in China are kind of the Jelly Bean cheap parts. Okay, at this point, all the high-precision stuff is being done here. And the only way people are doing this competitively is that they've automated and that's it. So the traditional machine shop model for pricing as they have a shop rate is and that's sort of everybody says our shop rate is x and it's just sort of their term. So when they price something, they sit down and they say how long is it going to take me to study the plans and figure out what parts I need to buy? How long is it going to take me to program it? How long is it going to take to get it set up? What's my scrap rate likely to be multiply it all up by their shop rate and they say here's the price and by the way, I can't deliver it for 14 weeks. And it fails in a couple of ways it fails because it doesn't actually apply the costs where the costs need to be. It's an informal way of pricing. And all the jobs that you're putting. Getting through there have 14 week lead times and everything drops into their normal sequence then probably works. But it's very inflexible.

One of the things that we did with one of our biggest suppliers is we got them all set up, what's not even our equipment, by the way, but they're set up to run lights out overnight. And we worked with them and said, Here's how you've quoted these parts at your shop rates running during the day. But think about what happens if you turn off the lights and they run all night long. If you really think that that constitutes your shop, right. And they did some analysis and they started thinking about it. They said, Yeah, we can run your parts at night when nobody's here. And it doesn't cost anything but a little bit of electricity, a couple of tools and some aluminum. And so consequently we can make a higher margin running your parts at night lights out, than we're making on normal jobs and, and still charge less for them. And that's where a lot of our suppliers have gone. And because it's not a way that a lot of shops are used to working thing is used to thinking, right, the concept of running lights out overnight. It’s really only been reserved for the very biggest shops with a lot of money, you spent a lot of money on very expensive equipment to be able to do that. Now the one company that's doing the bulk of our really high precision work that is doing that overnight, has very, very expensive, high production equipment. I'll toot our horn a little bit, you could be doing the same thing with our robots, a lot of our customers are and it's much less expensive now. But at the time they geared up to do this, that really wasn't available. So I'm not trying to turn this into a pitch of our robots. But basically, it is a pitch for automation, because that's the only way that we are going to end up being competitive is that is if the works automated.

[Sponsorship break]

Brent Donaldson: For more than 140 years, the LS Starrett company has been a leading manufacturer of precision measuring tools, gauges and metrology equipment recognized throughout the world for its exceptional quality, accuracy, craftsmanship and innovation. Starrett has earned a reputation as the world's greatest toolmakers. Starrett today proudly carries on its skilled tradition as the only company making a full line of precision measuring tools in the United States of America. Starrett: Measuring America since 1880, learn more at starrett.com/mia

[Sponsorship break ends]

Pete Zelinski: Here’s Jake Beahan.

Jake Beahan: When Productive Robotics started producing, one of our main goals was to keep it all here to reshore it all. We wanted to be made in America. We want to be American made and we want to be proud of what we were doing. And we had been through outsourcing overseas and the problems with it. There were cashflow issues with the size of the shipments you had to bring in. You had scheduling issues, you had shipping issues. It's just, we wanted to be made in America. And we did that by designing a new product from the ground up. Well, there are a few key things we learned in ZBE. And some of that is when you need to cut costs, you need to bring it in house. And you need to take the most expensive pieces that you're outsourcing and figure out how to do them yourselves. So when we started building robots, we hired this one consultant. And first thing he said is don't design your own gearboxes. And we said why? We're going to, we're going to design our own gearboxes, he goes, it's a long, long train to go down to design your own gearboxes, make your own gears, you should just buy an off the shelf one. And we started looking at off the shelf ones and they were just too expensive at the time for what we wanted to sell. We didn't want to enter the robotic market making a robot that cost the same amount as everybody else. We wanted to enter the robotic market making a robot that everybody can afford that small businesses could afford. And the only way we knew how to do that was to start from the ground up and design everything. And we knew we could design a gearbox and bring the technology in house to manufacture it. We weren't scared of that. It was just the amount of time that it took for us to actually do it was longer than we expected. There were a lot of failures along the way, a lot of gearbox testing, a lot of gear testing. And fortunately, we hired the right people to help us through it. We were lucky in that regard because ZBE was running, it was our sister company, we had full access to all their equipment. So you know, because the two companies had the same ownership. It wasn't a problem. We had everything we needed at hand. We weren't starting out of a garage. We had a CNC mill with a trunnion on it to make five access parts. We had access to a CNC lathe, we had manual lathes, manual Mills, we had everything we needed here.

Zac Bogart: Okay, well we made a conscious effort to move the work here. It was a little bit driven by some of the parts that we got in that weren't hitting the tolerances that we need. But that was not an insurmountable obstacle, our high precision shop that we use in Dongguan that we've worked with now for 15, 17 years. And a model facility can hit those tolerances. They weren't used to doing it for us, because we hadn't needed it in the past. So that was not an insurmountable obstacle. It was a contributing factor. Okay, so we made a decision that we wanted to bring the work here, and we wanted to bring as much as we could here, and so we picked those parts, which were the highest tolerance parts or the tightest tolerance parts, the most complex parts, and we moved in here, and they went to NCE. So that was the first wave of parts. One of the motivations that I'll point out was the Trump tariffs. Now, as an economist, you say that tariffs are generally really a bad thing, right? Tariffs generally restrain trade, the economic system doesn't function as well when there are tariffs clogging up the works. But in this case, and for the purpose that they were designed, which was to drive people, drive business and to drive manufacturing, back on shore, they have worked, and they've worked, at least from our perspective, they've worked very well. I don't generally approve of, I'm generally a purist capitalist. So I don't generally approve of things that generate restraints and trade. But I can say that they actually worked. Now, if all they did was raise the price of what was coming out of China. Well, China will start lowering some of their prices. But when you add up all the things together, the price increases the local suppliers being able to automate and bring their bring their costs down, and they're making it easier to work with them. When you add those things together, when you add the long lead times and the supply chain, and the complexity of that, and this is even before we're talking about before we're worried about COVID Supply Chain getting all clogged up, it all conspires, it all adds up to help make the decision that let's bring the work back here. The automation is coming in. And we're seeing it increasing literally by the month. And one of the things that we're seeing with the customers is that they don't quite completely grasp what it's going to do for them. The best analogy we can make, and it's so long ago that they almost laugh at it, is can you imagine can you remember when you went to using CNC machines from manual machines? Right, and the CNC machine makes all the parts and when you had to make them manually? That was an enormous change. But imagine the mindset that they had to get through to do that it took a decade, a decade or two and it took people retiring, who had older mindsets, it took people who are younger, who I won't, say were hipper and smarter, I will say that they just simply didn't have the historical background, to know that if something was any different, and that this was a change, the only way we're going to compete and get everything, well you're never going to get everything reshored. But the only way we're going to compete and bring as much back as we possibly can, is to knock the labor component out. And if we can lock the labor component out, then the onshore production has a fundamental advantage, rather than a disadvantage in the last two decades. The overseas suppliers had a fundamental advantage, right? The people worked for very inexpensively, the equipment was less expensive that they were using so that their overhead was lower. Everything conspired and added up to be able to produce these parts very inexpensively, now at the overseas end, their costs are going up. But they're still lower than ours, but fundamentally costs the same amount to buy the machine, the material that you put in the machine cost basically the same amount. Right? So what's the difference? The difference is the cost of doing the setup of the labor. Whether it's the setup or whether it's operating the machine. So if in this country or in any country, you got a person there operating a machine versus a machine that's operating itself and not needing that person, you can say goes right to the bottom line or you can say goes right into making you more competitive and you know, it's common for the economist to say that every time there's been a technology paradigm change towards higher automation and, and labor reduction, it's always increased the size of the labor force and the amount of production throughout history. And it's true. But the person who doesn't have the skill set to move into another job or doesn't think they have the skill set, that doesn't work for them. They don't want to hear that.

The target customer was basically automation. Machine shops are what we know, it's what we ran here, we know all the people around us that make parts for us. And it was just kind of a good fit for us. We're down the road from Haas. So we see the machines everywhere around here. So at any machine shop, you walk in around here has a Haas mill or lathe in it somewhere. And it was just an easy fit. And something that all of the history of the people here understood. First is we believe in no programming. So our robots are all done by teaching, you show them what to do, and then they repeat from you. So I can teach my kids how to use a robot in five minutes. In fact, they come in here and do it. The younger generations are used to working on cell phones. If you can use a cell phone, you can use a robot, it's that intuitive. There's no programming behind it, you don't need to understand if statements, while loops variables like you do in traditional robot programming. It's all done on a tablet so it's a very similar interface. Our next big differentiator is we have seven axes of our robot, the seventh axis allows the robot to reach around objects into things. The roll on your shoulder as the seventh Axi and without that you can't reach behind your back. So if you want to think about it, our robots can scratch your back for you. They can reach behind and Productive Robotics really believes in selling a complete package, a final solution to the end user. So with us, we're selling you everything you need to automate that Miller lathe, for instance. Whether it's an EDM machine or a router or a laser cutter or even a CMM machine, we're selling you everything you need to buy from us and automate it and go. You don't have to figure out how am I going to mount it? What end effector am I gonna buy? How am I gonna hook it up to my machine? We sell dozens of cables to hook up to different equipment that we figured out whether it's a Dusan, amazac, a Kuma, Haas, Bridgeport, it doesn't matter. We have the cables you need to hook it up. There's still a lot of people that believe Made in America is the best. And there's still a lot of people, when you go to a trade show, and they hear you actually manufacture in America and make robots and you say yes, and we have them in stock. We can deliver them next week, and they just can't believe it. And they go you mean you're designed in America, right? And you go, no, no, we're made in America. We manufacture the parts here in the United States. We assemble them in Santa Barbara, California, and we ship them out. The look on people's faces, they just can't believe it sometimes. But it's a good feeling to be part of something that's making a difference.

And I love hearing the stories from robot owners about how it's helped their business and how they're more profitable than ever having robots in there that are working alongside their other employees making parts for them.

Brent Donaldson: Made in the USA is a production of Modern Machine Shop and published by Gardner Business Media. The series is written and produced by me and by Peter Zelinski. I mix and edit the show. Pete also appears in our sister podcast all about 3d printing or additive manufacturing. Find an AM radio wherever you get your podcast, our outro theme song is by The Hiders and speaking of The Hiders stick around after their song ends to hear an anecdote from Zac Bogart about how the crew that did special effects for Close Encounters of the Third Kind was able to create the ominous cloud effects during the movies creepy first alien invasion scene. If you enjoy this episode, please leave a nice review. Seriously, for better for worse, it's really helpful if you actually liked the series to leave a five star review. So thank you so much. If you have comments or questions, email us at made in the USA at Gardnerweb.com Or check us out at mmsonline.com/madeintheUSApodcast.

Zac Bogart: I was working for a company called Future Gen, which was a r&d company that was owned by Paramount Pictures. And I happened to know the guy who was running it, had been a family friend. His name was Doug Trumbull. He did the special effects for 2001. When I was in 10th grade or 11th grade, I guess my dad said, Hey, call Doug, see if you can get a job, you know, working around his place cleaning up or doing something, you know, and a summer job. So I got a summer job there. And they were doing a lot of development of new technology, one of the new visual effects and things one of the things that they pioneered was what was equivalent of flight simulators, but for entertainment and you're watching a movie, they're common now. When I was in high school, I actually designed electronics for the very, very first one, when I was in high school, didn't work all that great, because I didn't know that much about what I was doing. But it worked. It worked. And so anyway, when Star Wars came on, half of the company left and went to Star Wars and right at the same time, Close Encounters was starting and the other half of the company did Close Encounters, the company did Close Encounters. And so I was lucky enough to get at the same time jobs working on both at the same time. So I was working at weekends on the Star Wars crew and I was working during the week on the Close Encounters crew. So I just was really, really lucky to do that.

In Close Encounters, every one of the cloud scenes, you know where the other clouds that are forming and just forming I worked on all the shoots. Okay, we have a tank with a big giant glass tank. Because no computers, giant glass tank, and we filled the bottom half with cold saltwater, and the top half with hot freshwater, and very, very carefully and it formed an inversion layer between the two layers of water. So we filled the tank that way, it took hours to get it filled. And then he had a big long, I don't know, an equivalent of like a hypodermic needle, but a big long thing with a tube. And he could go in there and drop some white paint in there. And then it would spread out while we were shooting it. I got chewed out for smoking and too close to the thing because they didn't want any other cigarette smoke floating into the end of the thing. And so we'd get one shot off of that one try. And then the whole tank would have to be drained, cleaned, washed, refilled the next day for the next shot. So it took a long time to time to do it. But Doug, who was the director doing it was just visually a genius. And it looks really good. It looks really real.

Related Content

Which Approach to Automation Fits Your CNC Machine Tool?

Choosing the right automation to pair with a CNC machine tool cell means weighing various factors, as this fabrication business has learned well.

Read MorePartial Automation Inspires Full Cobot Overhaul

Targeting two-to-four hours of nightly automation enables high-mix manufacturer Wagner Machine to radically boost its productivity past a single shift.

Read MoreWeiler to Debut New Automation Features For Its Lathes

Weiler’s V 110 four-way precision lathe introduces features new to the U.S.

Read MoreUsing the Toolchanger to Automate Production

Taking advantage of a feature that’s already on the machine tool, Lang’s Haubex system uses the toolchanger to move and store parts, making it an easy-to-use and cost-effective automation solution.

Read MoreRead Next

The Cut Scene: The Finer Details of Large-Format Machining

Small details and features can have an outsized impact on large parts, such as Barbco’s collapsible utility drill head.

Read More3 Mistakes That Cause CNC Programs to Fail

Despite enhancements to manufacturing technology, there are still issues today that can cause programs to fail. These failures can cause lost time, scrapped parts, damaged machines and even injured operators.

Read More

.jpg;width=70;height=70;mode=crop)