By the time your company invests $3.4 million and 11 months to dig a 45-by-75-by-7-foot pit, fills it with crushed stone and concrete, and tops that with a massive five-axis machine, it is more than likely your operation has experience machining extremely large parts.

That is certainly the case for Baker Industries, a subcontract manufacturer that primarily serves the OEM and Tier-One aerospace and automotive sectors. Baker Industries is located on a vast industrial campus housing several complexes in the Detroit suburb of Macomb, Michigan. And inside one nondescript building on the corner of campus you’ll find a true metal giant — a five-axis vertical machining center with a work table large enough to double as a car pad for a fleet of full-size SUVs.

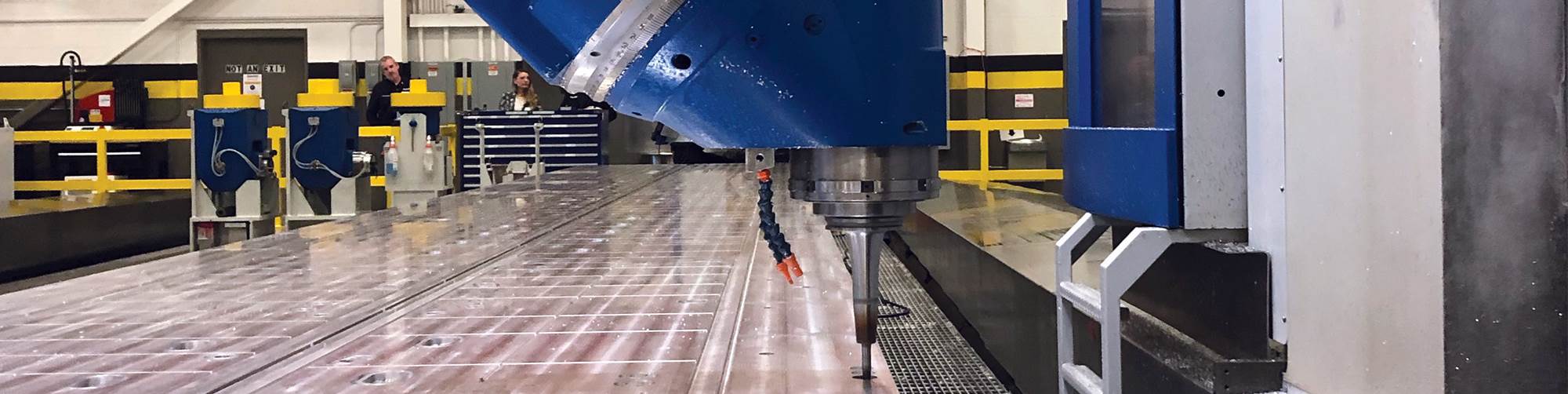

Baker Industries’ newest and biggest machine is the Emco Mecof PowerMill, an investment that has expanded the company’s capacity to serve its customers’ largest machining projects. The installation process was necessarily complex, starting with the removal of 1.2 million pounds of concrete and earth to excavate the gargantuan pit. Each truckload of the nearly 2 million pounds of crushed stone and concrete had to be individually sampled by inspectors to ensure it was the right consistency — an extra precaution for a reinforced foundation that has to remain stable beneath an overhead gantry that alone weighs more than 100,000 pounds. The bridge and columns of the PowerMill seem to travel effortlessly along a 52-by-20-by-10-foot XYZ work envelope.

There is a reason that Baker Industries is one of the only companies in the U.S. that has invested in a machine of this size, and that reason has everything to do with experience. Before the company brought the PowerMill online, it had already been operating a 32-foot horizontal five-axis Emco EcoMill as well as a handful of Breton five-axis machines that measure up to 27 feet along the X axis. As Baker Industries program engineer Jerry Kablak pointed out during my recent visit to the company, maintaining a tolerance of two-thousandths of an inch for a part that measures 30 feet or longer involves more than just scalability. It involves extensive training and the incremental knowledge that comes with years of experience with uniquely complex setups and programming. Here is how that experience became evident during my visit, when the PowerMill was in the final machining stages of a large aerostructure component that was more than 40 feet long.

Setting the Stage

The first thing you notice on Baker Industries’ sprawling campus, where nearly 300 employees work across five facilities and 250,000 square feet of space, is the security measures that have been put in place. As Mr. Kablak explains, these measures extend not only for the employees’ safety, but also for the company’s data and equipment. Each of the five buildings on campus is accessible only to certain employees, which is not unusual. But while walking through the building that houses most of its machining centers, it is hard not to notice that most of the make and model numbers of the machines have been covered with Baker Industries’ own logos — an extra layer of information security to guard against prying eyes.

When walking through this building, you can almost see an evolution in size and scope taking place among company’s 35 CNC machines, from smaller vertical three-axis mills, to the (much) larger Breton five-axis machines, to the massive Emco EcoMill. But, situated between a massive American flag and a giant Modern Machine Shop “Top Shops” banner (the company won the award in 2018), the PowerMill looms above them all; its massive work envelope taking up nearly half of the building that houses it.

The PowerMill’s table has a load capacity of 2.6 million pounds, much greater than the weight of the eight aluminum workpiece plates that stretched across it 40 feet from end-to-end during my visit. When finished, these plates will be assembled together to form a layup mold for an aerostructure component, although no one at Baker Industries was willing to say exactly what the final component was destined to become.

For all of the mass that the PowerMill represents, the machining center giant can achieve almost shocking precision, able to maintain total error of less than 42 microns along its entire 46-foot-long X axis. This is largely due to the laser trackers that are positioned on the gantry’s two columns. These trackers can be used to help fine-tune the setup process, then continuously scan the workpiece during machining to ensure accuracy is maintained from beginning to end.

Programming the PowerMill is all the more complex when you consider not only the automated tool changing that the machine is capable of, but also the four separate, interchangeable cutting heads that can be utilized for different operations. These heads are powered by spindle motors that reach up to 18,000 rpm, which enable the machine to handle roughing to semi-finishing to finishing all in one setup. Of course, these capabilities make proper setup all the more vital. As Mr. Kablak told me, locking down the proper setup procedure was one of the biggest learning curves for Baker Industries’ larger machining centers. “Even at a smaller scale when you have smaller machines, the same issues are there,” he said. “So on a machine like the PowerMill, you can imagine how all of those issues are amplified.”

Of course, the nature of the work that requires a machine like the PowerMill is much more likely to be for one-off or low-volume parts, which means that there is no cookie-cutter setup procedure that Baker’s machine operators can rely on. Before the company had the PowerMill and EcoMill in place, Mr. Kablak says that he and his colleagues had gained years of experience machining large parts by creating multiple setups for the workpieces, flipping them over and ultimately passing them through the open doors of smaller machining centers.

Baker Industries’ general manager Bill Ednie told me that the workpieces being machined on the PowerMill during my visit required more than a week to set up, as well all a lot of forethought into how to ensure that each plate was properly stress relieved to reduce the risk of warpage before machining operations began. The vacuum grooves on each of the eight plates had already been machined, and the final step before inspection began was to drill the holes that the customer would use to lock the pieces into place for molding operations.

Of course, even though Baker Industries is one of the few companies in the United States to have a machining center this massive, that doesn’t mean there will be year-round production needs for parts large enough to take advantage of its size. As Kablak colorfully puts it, the company invested in this monster of a machine, and it needs to be fed. The question then becomes: How do you make sure it does not go hungry? The answer is creativity.

Build It and They Will Come

Here is one example of creative thinking that helps keep the PowerMill fed and its spindles turning. Before the end of my visit, Mr. Ednie pointed out an attachment for the PowerMill that took advantage of Baker Industries’ in-house 3D printing capabilities. The company began investing in additive manufacturing (AM) technologies in 2014, and today has seven 3D printers, most of which are Stratasys fused deposition modeling (FDM) machines for plastics, in addition to two EOS direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) machines.

The attachment is a right-angle bracket for a cutting head that contains internal channels for air-cooling passages. By shooting air directly onto the attachment and the workpiece, Mr. Ednie says the cutting head can operate for hundreds of hours on end.

But Mr. Kablak says that the primary method of keeping up with the appetite of a machine like the PowerMill is to set up multiple jobs on its table at once — or to machine a part on one end of the table while setting up another job on the other end. “And I don't mean very small workpieces,” he says, “but things that would that could potentially fit on a 10- or 20-foot table. We can put three or four of those on this machine, and as we're laser checking while setting up one job, we can be machining since there's so much room there. Feeding the machine has definitely been a challenge, but there is always a way to overcome that challenge.” He estimates that this solution accounts for as much as 20% to 30% of the PowerMill’s work.

Like the gradually expanding size of the machining centers owned by Baker Industries, the growth of the business itself — from its co-founding by brothers Scott and Kevin Baker as Baker Duplicating in 1992 to the operation it is today — has been incremental. (Note that Baker Industries was acquired by Lincoln Electric this year.) The company did not purchase the PowerMill because of the promises of any single potential customer. Mr. Kablak says that, once the company went public with the news about its investment in this machine, the requests for quotes soon followed — especially with automotive and aerospace customers that require large parts.

“Our first five-axis mill was of modest size,” he says, “and then from there, the machine sizes kind of slowly built up. We never had jobs that were promised to us if we had the larger equipment. That never happened. When we make these kinds of investments, we put the word out and wait to get a return on that investment with increased workloads. A lot of it comes down to, if you make the investment, the work somehow does find you.”

Still, Mr. Kablak says, he would encourage any company with the capacity to invest in large equipment like the PowerMill to explore the opportunity to diversify its scope of work. The key is to have a core set of customers before making any decisions. “If you're really, really deep in with one customer and then make a big investment like this, if that customer doesn’t come through, it could sink you,” he says. “So my advice is to have your business plan together, make sure you are diversified with multiple customers, and make sure the opportunities are out there. And then I would say just go for it.”

Related Content

Inverting Turning and Five-Axis Milling at Famar

Automation is only the tip of the iceberg for Famar, which also provides multitasking options for its vertical lathes and horizontal five-axis machine tools.

Read MoreWhen Organic Growth in Your Machine Shop Isn’t Enough

Princeton Tool wanted to expand its portfolio, increase its West Coast presence, and become a stronger overall supplier. To accomplish all three goals at once, acquiring another machine shop became its best option.

Read MoreIMTS 2022 Review: Attention to Automation Extends Beyond the Robot and the Machine

The advance toward increasingly automated machining can be seen in the ways tooling, workholding, gaging and integration all support unattended production. This is the area of innovation I found most compelling at the recent International Manufacturing Technology Show.

Read MoreA New Milling 101: Milling Forces and Formulas

The forces involved in the milling process can be quantified, thus allowing mathematical tools to predict and control these forces. Formulas for calculating these forces accurately make it possible to optimize the quality of milling operations.

Read MoreRead Next

Running Unattended at Night Lets Machine Shop Serve New Customers During Day

Precision Tool Technologies found capacity for diversification not by adding machines, people or space, but by freeing up time. Running unattended—running so it can machine through all 168 hours in the week—has enabled this shop to use hours when staff is present to deliver work that lands outside its established specialty. To achieve unattended machining, some of the biggest challenges have related to basic details such as chips and coolant.

Read MoreTop Shops Winners Talk Technology, Tactics

Successful machining businesses implement effective processes and strategies both on the shop floor and in the front office. Recent chats with representatives from this year’s award-winning Top Shops shed light on some approaches they have leveraged to their advantage.

Read MoreTackling the Aerospace Supplier’s Dilemma: Scalability

Automation and robotics can go a long way toward increasing capacity and growing a business dedicated to aerospace manufacturing. But Trinity Precision has learned that refining the indirect and unseen aspects of its operations can be just as valuable.

Read More