Share

Machining components for surgical tools is complex work, but Metal Craft prefers a simpler approach to automation. “We just want it to load the machines, so our people can go and do something else,” says Jeff Thrun, general manager.

The Profeeder robot cell from Easy Robotics significantly reduced the engineering effort that would be required to develop a part-staging system in-house. As detailed below, the shop has also added its own methods of part staging. Photos by Peter Zelinski.

Limiting the use of robots to machine tending contrasts starkly with the recommendations of many outside integrators, Thrun says. “They’ll say, ‘Just tell us what you want done, and we’ll turnkey it in our facility and deliver it to you.’ I’ll say, ‘Great, you can put it there on Monday, and I’ll call you back on Wednesday, because that job will be done.’”

In other words, loading and unloading parts is low-hanging fruit for Metal Craft’s collaborative robots. More ambitious work – say, deburring or inspection – might be possible to automate in some cases, but part quantities are often too low and process variability too high for it to be practical. A more limited approach results in a process that still requires attention, but not at the cost of an idle machine tool spindle. “A person has to go over and do the quality inspections, do the SPC [statistical process control] charting, change the tools when they meet their tool life expectancy, and that kind of thing – that doesn’t change,” Thrun explains. “But now, they can run two or three machines instead of one.”

Holding tolerances measured in tenths on parts like this surgical tool assembly component requires the shop’s smallest cutting tools and most precise five-axis machine tool.

This focus has made automation easier to implement, but the team also has made extensive efforts to ensure seamless changeovers from job to job. One result of this work is a modified part-staging system that flexes as-needed to accommodate different-sized workpieces. Another, more recent example of how repeatable setups help make the most of automation involves not a robot, but a pallet changer. In this case, job changeovers are a matter of simply “picking one pallet up off the (conveyor) chain and putting another one on,” Thrun says.

Experience with both robots and pallets has enabled the shop to evaluate the relative merits of both systems for its applications. Those merits aside, the broader lesson of Metal Craft’s journey is that a varied mix of complex work need not deter any manufacturer from automating, whether with robots, pallets or both. As Thrun puts it, “these are just two different ways of delivering parts to the machine.” Success depends on how they are used – and, increasingly for this Minneapolis medical manufacturer, the equipment to which the automation is attached.

Jeff Thrun, general manager at Metal Craft, explains one of the company’s first robot automation applications: for high-volume electrical discharge machining (EDM). Now, less expensive, easier-to-program collaborative models that require no caging are beginning to populate other areas of the machine shop floor.

Unattended Only, Please

A tour of the 83,000-square-foot shop floor quickly reveals one of this 150-employee company’s most striking characteristics: For most of its history, machining has depended as much on the machinists as the machine tools. Thrun cites expertise with setups and workholding as critical to weaning the maximum capability from milling and turning machines.

In addition to precision machining of individual components, Metal Craft offers Design for Manufacturing (DFM) as well as assembly of complete surgical tools from its Minnesota facility. A nearby sister company, Riverside Machine and Engineering, focuses more on aerospace work.

The difference today is that a phrase like “milling and turning” is more likely to describe the same machine. Bar-fed turn-mills have become more common, as have five-axis machining centers, because consolidating setups improves both the quality and the speed of machining.

Both goals are critical because customer requirements are changing, Thrun says. That goes not for just the work itself, but also demands surrounding it, such as increased inspection requirements. Meanwhile, machinists remain as hard to find as ever. “In order to grow, we need our people to accomplish more without working any harder. We plan to do that through unattended machining.”

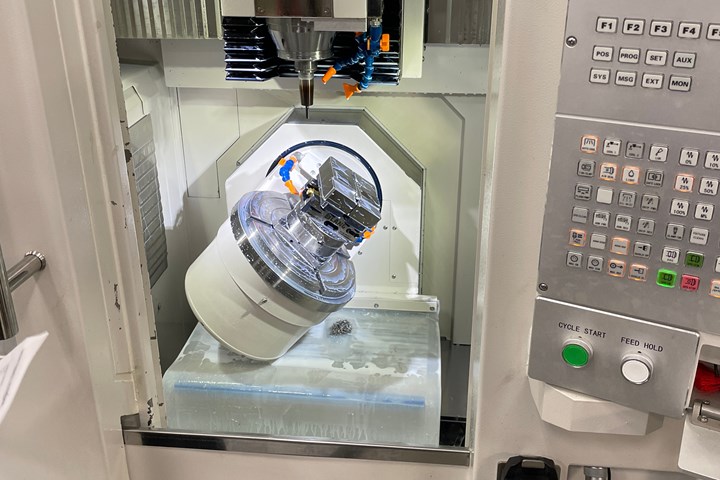

So far, the most significant investment toward meeting that goal is a pallet-fed five-axis machining center with capability that sets it apart from the rest of the shop. Capable of machining to accuracy of less than 2 microns and achieving nanometer-level surface finishes, the GRA200 from Jingdiao North America is also an unusual make and model for a U.S. machine shop generally. However, the builder is working to change that, and more broadly, to emphasize the role of high precision in ensuring reliable lights-out machining. In fact, Metal Craft’s opportunity to purchase the machine came with one condition: It would be displayed at IMTS 2020 first.

Based in China with a U.S. office near Chicago, Jingdiao specializes in high-precision machining. Metal Craft reports that ensuring quality parts is easier and faster with, among other capabilities, single-setup, five-axis processing; robust software simulation; and a 24,000-rpm, through-coolant spindle driving the shop’s smallest tools (some applications reportedly involving roughing with a 0.020-inch end mill).

When that event was cancelled, Metal Craft took delivery early. The machinists tasked with running the new machine made the most of the extra time, even opting to master the builder’s own CAM system rather than choose a more common option. Nonetheless, the machine “hit every bullet item flawlessly” in a six-month trial.

In addition to the machine itself, Metal Craft had to make the most of the pallet system that came with it. This provided an opportunity to test another form of automation against the shop’s first collaborative robot, where the team had already made significant strides in tending a less-precise machine.

Making Setups Repeatable

Thrun credits multiple team members for the success of that first robot, a UR-10 from Universal Robots. He also credits the integrator who sold it, PCC Robotics, for appreciating the challenges associated with an environment where a “high-volume” order amounts to only 100 parts at most. However, he says the effort really began with the hiring of a young automation engineer who started with Metal Craft as a college intern. In early attempts to maximize unattended machining time, he set the same goal for the robot that the machinists would set later with the pallet system: ensuring time spent setting up did not exceed the time spent cutting parts.

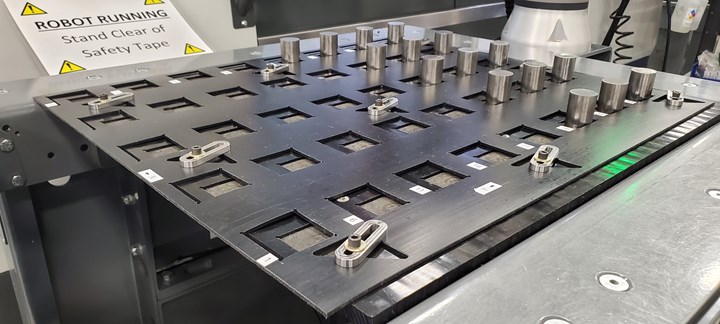

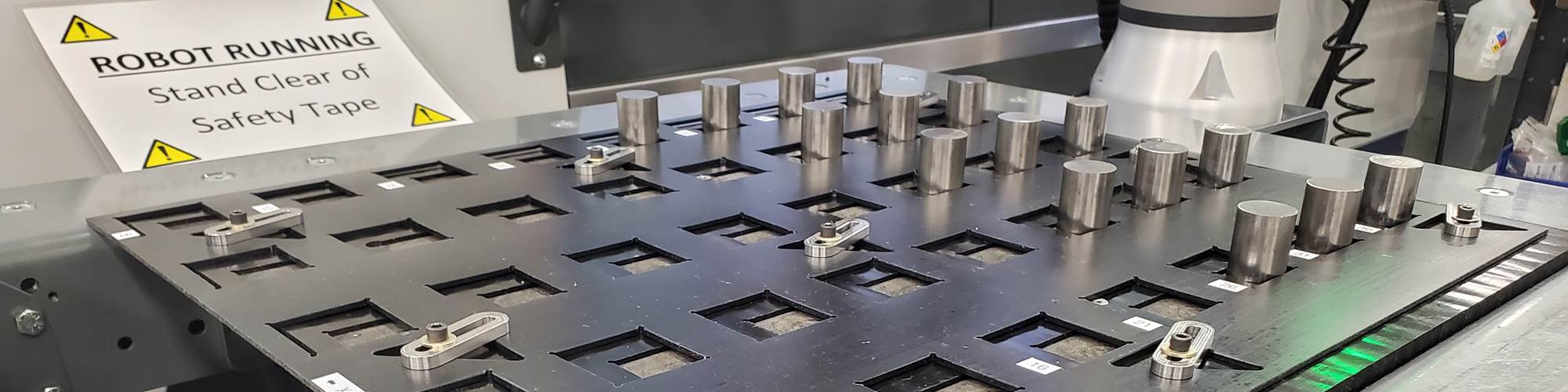

The system of overlapping trays visible here is an in-house modification. Sliding the top piece at an angle enables adjusting the size of the opening between 1/2 and 2 inches to accommodate varying sizes of stock while maintaining a repeatable part-to-part position increments for the robot. With programs and sets of 3D-printed jaws at the ready when a part order repeats, robot changeovers from one unique part number to the next generally take less than half an hour.

The solution was the same as well: ensuring repeatable setups and, by extension, seamless changeovers from batch to batch. The part-staging system implemented by the automation engineer, pictured above, will likely be replicated as the shop adds more collaborative robots.

A machinist demonstrates what it took to swap a setup prior to the addition of more workholding. Now, pallets are pre-staged.

As for the pallets, the basic idea is also to standardize on workholding and pre-stage setups as much as possible beforehand. To that end, the shop has invested heavily in pallets, 5C collets and two types of vise (a model from Lang Technovation that machinists appreciate for tool clearance, as well as a model from Jergens that they appreciate for a secure grip).

With workholding pre-configured and already mounted on the pallet and standard sizes for blanks, changing over to a new part is a simple matter of choosing the right-size collet or vise, and in the latter case, a new set of custom jaws. Generally, the only items to affix or remove from the pallets are the workpieces themselves.

“All things equal” comparisons of the two delivery mechanisms are easy for Metal Craft because they are seen as just that: delivery mechanisms.

Stretching Skills Further

Although the pallet system has more than paid for itself, Thrun says Metal Craft’s future is likely with additional collaborative robots, even as it plans to expand its capacity for fine-tolerance machining.

With one workpiece per station, he explains, the pallet-fed machine can cycle through 24 workpieces before someone has to attend to it. However, only half are likely to be finished parts, because even a five-axis machine requires a second setup for sixth-side operations. Barring an investment in a larger pallet changer (and more pallets to set up beforehand), a robot could conceivably cycle through more parts without intervention, simply because more parts can be staged in front of it. Running only one unique part number at any given time also makes robots a better choice for avoiding line clearance issues – that is, avoiding mixing between jobs, which can be a hazard for quality control.

Regardless, focusing too much on the merits of either system risks missing the point. “All things equal” comparisons of the two delivery mechanisms are easy for Metal Craft because they are seen as just that: delivery mechanisms. Which part runs where depends not on the robot or pallet system, but on the machine itself. Suffice it to say, Metal Craft plans to install another five-axis Jingdiao, although this machine might be fed by a collaborative robot rather than a pallet system.

Related Content

How to Determine the Currently Active Work Offset Number

Determining the currently active work offset number is practical when the program zero point is changing between workpieces in a production run.

Read MoreAdditive/Subtractive Hybrid CNC Machine Tools Continue to Make Gains (Includes Video)

The hybrid machine tool is an idea that continues to advance. Two important developments of recent years expand the possibilities for this platform.

Read More4 Commonly Misapplied CNC Features

Misapplication of these important CNC features will result in wasted time, wasted or duplicated effort and/or wasted material.

Read MoreControlling Extreme Cutting Conditions in Large-Part Machining

Newly patented technologies for controlling chatter and vibration during milling, turning and boring operations promise to drastically reduce production time and increase machining performance.

Read MoreRead Next

Preparing a Shop for Automation

Ensuring a stable, predictable production process can prevent automation from multiplying existing problems.

Read MoreFocus on Throughput Empowers People and Machines

Lessons learned in robot-tending coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) translate well to a self-correcting multi-tasking machining process.

Read MoreOEM Tour Video: Lean Manufacturing for Measurement and Metrology

How can a facility that requires manual work for some long-standing parts be made more efficient? Join us as we look inside The L. S. Starrett Company’s headquarters in Athol, Massachusetts, and see how this long-established OEM is updating its processes.

Read More

-02.jpg;maxWidth=300;quality=90)