Combination Machines Changing The Toolroom

There's a relatively quiet but relentless change in metalworking toolroom equipment. Handwheels are still there, so manual operation is preserved, but now there is the capacity to operate these machines automatically via CNC or using a combination of manual and CNC. Timing for this additional flexibility is perfect.

Share

Technology, in the form of combination machines, is stepping into the vacuum formed by the shortage of toolroom machinists. In shops where the machinist shortage is less acute, combination toolroom machines are helping shops be more productive.

Driving this sea of change within toolroom equipment is the continuing development of inexpensive yet capable computer controls. Equipped with these flexible CNCs, the ubiquitous toolroom machine is evolving into a new class of technology across milling, turning and grinding operations.

Many of the skill sets that traditionally resided in the minds and hands of toolroom machinists can be found in the computer, attached to these new toolroom machines. A prime advantage for the shop using this technology is the ability of personnel with varying skill levels to operate these machines.

Application of flexible CNCs that can emulate manual operations, be operated in a semi-automatic teach program mode or operate automatically under full CNC is helping toolrooms cope with the pressures of delivery, quality, and throughput that are daily realities in metalworking shops.

We talked to several builders of toolroom mills, lathes and grinders to get their take on the move toward more operationally flexible toolroom machines. Here's a look at this new and interesting metalworking trend.

What Are Combination Machines?

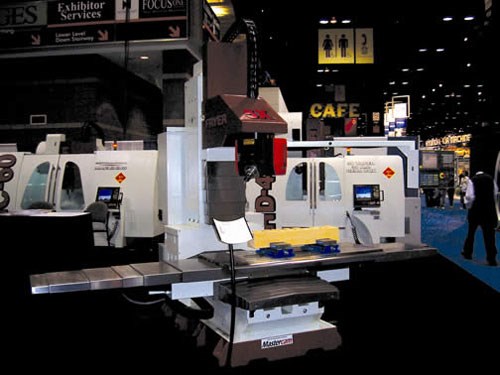

Combination machine tools occupy a niche between manually operated machines and fully enclosed CNC machining centers, turning centers and grinders. Generally classified as toolroom machines, combination machines represent a bridge between manual and CNC operation.

The machines offer a unique set of capabilities to shops looking to transition from manual operation to a more automated mode. Flexibility of programming techniques is a key factor to the success of combination machines.

Combination machines are computer controlled and programmable online or off-line. In that respect, they are no different from a CNC machining center or turning center. However, they also possess a third programming option that is unique to the combination machine.

One difference between combination machines and CNC machining and turning centers is that combination machines, when desired, can be operated in a fully manual mode using handwheels. Because the handwheel is either mechanically or electronically linked to a ballscrew, any movement of the wheel registers on an encoder located on the servo.

This data acquisition allows the machine movements to be captured by the control. It's like reverse engineering a part program.

By machining a first article, a manually trained machinist can program the CNC to reproduce subsequent parts. In shops with short run work and a shortage of machinists, teach mode allows them to better utilize their highest skilled workers. Rather than assign a master machinist to run five or ten parts, he or she can run one and then move to another job.

"Combination machines are about transition," says Larry Fryer, president and founder of Fryer Machine Systems (Patterson, New York). "Many of the shops we put combination bed mills and lathes into are small businesses, most of whom are taking their first steps away from manual machines. Overcoming a fear of computer technology is a big step for many of these shops' toolroom machinists. Most of the new combination toolroom mills have handwheels that give machinists security that if all else fails, they can still make parts manually. In most cases, these shops are using partial or full CNC within a few weeks of taking delivery of a new machine."

Openness of the machine is another comfort factor for toolroom machines. "Toolroom machinists like to be near the cut," says Mr. Fryer. "Since most of these machines do not have automatic tool changers, pallet changers or tool turrets, guarding is minimal. The machinist can use his or her senses to monitor how the part is running."

"Toolroom machines have to be stout," says Tim Rashleger, COO at Milltronics, (Minneapolis, Minnesota). "They tend to be built more for endurance than speed. Often the work that crosses these machines is prototype or short run jobs. There is rarely a chance to optimize tooling, feeds or speeds. Therefore the machine has to be able to absorb punishment from processes that are much less refined than can be achieved on longer runs."

Combination Mills

The toolroom milling machine workhorses are still the knee-mill and bed-mill. The basic design for these machines has been around for many generations. However, application of CNC and servo drives to these machines has allowed enhancements that make these classic designs much more productive.

An example is the knee mill. Early attempts at putting axis drives on these machines were hampered by the quill. This left knee mills with CNC limited to two-axis operation. A manually operated quill provided the third axis.

An advance in the classic knee mill design came with the application of a servo-controlled slide attached to the milling head. According to Mr. Rashleger, "this advance, we call Millslide, allows the quill to be operated manually while offering a third axis motor controlled by the CNC to be turned on or off at operator discretion. In a drilling operation for example, the manual quill can be quickly positioned to touch the workpiece, then locked. The Z-axis servo can then be actuated to drill the hole."

Bed mills too have received upgrades that leave some of their manual machine heritage behind. An example can be found on Fryer's VB series of bed mills. "On this machine we basically put a machining center spindle carrier on a bed mill frame," says Mr. Fryer. "Without a quill, it provides shops with better rigidity and accuracy. It's basically a machining center with the `friendliness' of a bed mill."

Operating combination milling machines is designed to be easy. Operation is also designed to be flexible in order to accommodate different levels of skills found in the modern toolroom.

Take cutting a radius, for example. In most cases, a machinist only has one shot at getting it right, so processing options make the job a bit easier. Manually, the machinist must hook up a rotary table, bring in sine bars and scribe the radius to be cut. Then the machinist must work the X and Y-axis handwheels to get the final shape.

"Or," says Robin Baker of control builder Anilam (Miramar, Florida), "you can fixture the part, plug in the radius value in a macro-block on the CNC, move the tool to a start point and cut the radius. It's a much faster way to do the operation. If there is a small run of parts, CNC has better repeatability than manual operation, and each program segment you created can be stored for future use."

Combination Lathes

Combination lathes have their roots in the flatbed or engine lathe. That is the machine design traditionally found in the toolroom.

Equipped with a toolpost or sometimes a small indexable turret, combination lathes are differentiated from manual machines and turning centers by CNC control and servo-axis drives. Like manual machines, they have handwheels to control the X and Z axes manually. However, most combination lathes use electronic handwheels rather than mechanical.

Like combination mills, lathes use specially developed CNCs that permit a machinist to select one of three programming methods. Combination lathe controls provide numerous canned cycles for the operator to quickly create all or some of a part program.

According to Joe Felicijan, vice president of sales for Clausing (Kalamazoo, Michigan), lathe operators like to use handwheels. "Combination machines, using electronic handwheels, allow the machinist to turn one handwheel that then drives the other. An example of this master/slave operation is cutting a taper. The machinist feeds the tool manually while the CNC automatically interpolates the taper. This combination method works for threads and most other complex turning operations."

The program to cut the taper or other features can be created by teach method, by manual data input (MDI) or programmed into the control off-line via Ethernet. Programming flexibility is the deliverable that combination lathes bring to toolroom applications.

Combination Grinders

In grinding, the combination machine concept is being applied to toolroom surface, OD and ID grinding machines. For grinding, much of the success of combination machines has been in simplifying setup and improving cycle times.

A challenge for grinding machine builders is to try and bottle the arcane parameters of grinding in an MDI control. In doing so, they must take into account the varying skill levels of grinding machinists found in toolrooms today.

Touch and teach is the system that Okamoto Corporation (Buffalo Grove, Illinois) uses on its line of combination surface, OD and ID grinding machines. "The idea of our system is to create a machine and control combination that possesses knowledge about the art of grinding," says Ed Weinberg, manager technical sales at Okamoto. "A skilled machinist is free to manually override any of the parameters in the control, but the less skilled operator has fall back processing information if needed."

A significant amount of a grinding job's run time is devoted to setup. On traditional hydro/mechanical toolroom machines, this involves setting trip dogs for table traverse on surface and OD machines. Critical feed stops on ID machines need to be set.

"Electronic servo control on combination machines saves significant setup time compared to hydro/mechanical grinders, says Mr. Weinberg. "For traversing the table, a left and right dimension is entered into control. That's it. Dressing is also a teach function. MDI controls have made these new machines much easier to use by machinists with varying skill levels and have made big improvements in toolroom productivity for ground parts."

Toolrooms Are Us

Toolroom work is critical to the productive capacity of the shop, whether the assignment is creating one off jigs, workholders, or backing up production as a secondary operation. Almost universally, the toolroom is where the highest skilled machinists can be found.

These machinists are able to take even a relatively crude sketch and create a viable part from it using their eyes and hands to control manual machine tools—mills, lathes and grinders. They instinctively know how to machine and massage metal to get form and function from a blank. They know how to coax a machine tool to cut in ways that transcend technology and approach art.

Unfortunately for shops of all stripes, these metalworking artisans are a rapidly vanishing breed. The average age of a master machinist is the mid-fifties. With apprenticeship programs virtually non-existent in the United States, a large-scale ability to replace classically trained machinists is close to nil. Combination machines are helping shops fill the void.

Related Content

Milltronics Five-Axis Machining Center, Control Enhance Productivity

Milltronics USA Inc. introduces its first five-axis machining center, the VM250IL-5X, as well as its machine control, the Inspire+.

Read MoreCan AI Replace Programmers? Writers Face a Similar Question

The answer is the same in both cases. Artificial intelligence performs sophisticated tasks, but falls short of delivering on the fullness of what the work entails.

Read MoreGoing Hands-On with Heidenhain and Acu-Rite Solutions

Heidenhain and Acu-Rite Solutions are offering several hands-on experiences at their booth this year, as well as internal components that reduce energy use.

Read MoreFANUC Details Robotic Vision, ROBODRILLS and More at IMTS 2024

FANUC’s IMTS 2024 booth includes real-time demonstrations that show the abilities of its equipment, including robots, controllers and machine tools.

Read MoreRead Next

OEM Tour Video: Lean Manufacturing for Measurement and Metrology

How can a facility that requires manual work for some long-standing parts be made more efficient? Join us as we look inside The L. S. Starrett Company’s headquarters in Athol, Massachusetts, and see how this long-established OEM is updating its processes.

Read More