Low Cost Turning Automation Yields A High Rate Of Return

Two CNC lathes, with live tooling, tool monitor, and auto-load short-bar bar feeders are helping this California manufacturer compete. They've seen impressive reductions in throughput time and manufacturing costs. And, they're just getting started.

Share

Business is good for 25-year-old Matthews Studio Equipment, Inc. (Burbank, California). They manufacture "grip" equipment (clamps for lights and shutters), camera stands, lighting stands, and other photographic and lighting equipment used by the motion picture industry. Amazingly, with the thousands of these products that are sold each month, one wonders where they all go.

"In the old days," says Matthews' manufacturing manager, Bob Queenen, "the studios would usually make most of their grip equipment, lighting stands, and camera mounts themselves. Each studio had its own machine shop."

A problem with this approach was that it created a general lack of any kind of standardization or interchangeability of equipment. As a result, one studio's lights wouldn't fit another studio's stands.

"Our business was built on standardizing this equipment-taking over its manufacture-and then selling or renting it to studios or production companies," continues Mr. Queenen. It saved them the hassle of making the equipment and allowed the industry to have standard equipment to work with. As with most good ideas, others soon joined the ranks.

Matthews is in a very competitive industry where prosperity-even survival-depends on continuous methods improvement and cost reduction. It was that competition, according to Mr. Queenen, that caused this 75-person shop to look at ways to wring out manufacturing costs.

1500 Part Numbers

Overall, between Matthews' two primary metalcutting departments, the shop processes more than 1500 different part numbers. These range from small, screw machine types of parts to large castings. They cut primarily in mild steel and aluminum.

The turning department works with bar stock that is 5/8 inch to 2 inches in diameter. Lot sizes are generally around 500 pieces but can grow to 5,000 pieces for some jobs. Surface finish requirements are as low as 32 rms but generally fall in around 60 rms.

Tolerances for most of the workpieces are 0.001 inch. The shop has a milling department in addition to the turning operation. They operate two shifts each.

Matthews keeps track of its 1500 jobs with a material requirements planning (MRP) system. They build to stock so the MRP schedules jobs based on inventory and usage history. When the raw stock for an order is received, routers and setup sheets are issued to the shop and production begins.

One Setup Operation

An important goal for Matthews, as they investigated process alternatives, was significant reduction or elimination of multiple handling of the turning department work. As Mr. Queenen puts it, "We used to chuck our parts. We'd saw the blanks to length, bring them to the lathe, load the lathe, and then turn the first end using hard jaws. We'd then change to soft jaws for second-end operations. Our lathes would sit idle while loading and unloading the work, and while all this was going on, chuck jaw change-over took place."

Any secondary operations had to be performed at another machine tool. That added another handling to the work-in-process. (More about that later.) It was too much handling and setup time for Matthews to remain competitive.

To achieve the single setup goal, Matthews' first decision was that chucking the workpiece was too inefficient for the volumes of work they were doing. That decision led them to investigate bar feeding as a solution to improving productivity on their lathes.

Matthews purchased two SMW short-bar bar feeders. This relatively new type of bar feed is becoming very popular with shops that have never used bar feeders in the past, for several reasons. They're inexpensive, they're easy to operate, and they are very effective at reducing cost on medium- to short-run work due to their quick change-over features.

Matthews needed the reduced space requirements that these bar feeds offered. A relatively small footprint had a minimum impact on the shopfloor work flow and machine arrangements.

Second Ops

Secondary operation was another potential area of process savings for Matthews. Using a bar feed and collet arrangement allows the workpieces to be turned complete.

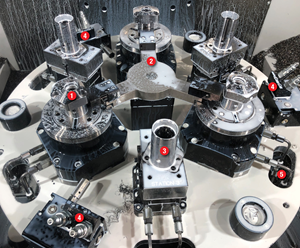

The turning centers that Matthews purchased are Okuma Cadets. These lathes are equipped with live tooling. "Several of our jobs have cross-drilling and other milling operations," says Mr. Queenen. "Our live tool stations allow us to eliminate a secondary operation on those parts."

Another benefit to the shop of producing workpieces complete on the lathe is the additional capacity that is available on the secondary operation machine tools. "The drills and mills we had to use for the secondary operations are now free to do additional production work," says Mr. Queenen. "It's an incremental increase in capacity."

The lathes have 12 live tool stations that are powered by a 3-hp motor. Maximum rotational speed for each mill/drill is 3800 rpm. "For our parts mix, we use only four turret stations for rotary tools," says Mr. Queenen. "That capacity allows us to use a drill and mill and still have a redundant cutting tool for both milling and drilling to use for unattended operation."

Making It Work

Anyone involved in manufacturing knows that changing a process, be it a subtle change or dramatic change, almost always introduces unexpected variables. In Matthews' case, the transitions from chucking to bar feed and from manual to CNC turning were fairly smooth. Credit goes to Mr. Queenen for good planning, and credit also goes to the machine tool and bar feed vendors who helped get the two turning systems up and running.

Programming is done at the machine and programs are then stored on diskette. "We basically program a job as it comes up in our MRP schedule," says Mr. Queenen. "Once we capture the program data on floppy, we've got it forever."

Matthews has had one of the Okuma/SMW turning center bar feed systems for two years and the second one for about a year. Program interchangeability is a plus, allowing them to move work between the two turning stations.

Turn Out The Lights

Matthews' increased productivity and automated operation from the combination of bar feed and CNC lathe freed the turning department to try operating a "lights out" shift. By eliminating the need to chuck parts on the turning center, bar-fed blanks could be machined complete without the time and labor-intensive need for loading and unloading.

"Switching to bar feeding allowed us to machine the entire piece in one setup, plus the automatic loading feature of the bar feeder allows us to run machines unattended," says Mr. Queenen. "In addition, we eliminated the cost of sawing blanks. Collectively, these savings have had an extremely positive impact on our bottom line."

As Mr. Queenen puts it: "We simply load the bar feed tables at quitting time, and the next morning we are greeted by 600 to 700 parts that were produced at very low cost. To optimize the number of parts we obtain, our lathes are equipped with a tool-wear sensing system that indexes a sharp tool into position as required."

The sensor on Okuma's lathe consists of a strain gage attached to the tool turret. It is programmed to detect additional strain on the cutter and holder that is created when a cutting edge gets dull. At a preset level of strain, the turning center automatically indexes to a redundant cutter. Several other advantages accrue from the fact that the lathe/bar feeder combination processes short bars that are 5 feet in length or shorter. Compared to 12-foot-long bars processed on conventional full-length bar feeders, the short bars are easily handled by one person compared to two people and sometimes a power hoist.

Although bars up to 3.15 inches in diameter can be run on the bar feeders, Matthews turns stock only up to a maximum of 2 inches in diameter. Also, the shorter length bars do not require any end-preparation such as squaring or chamfering. Because of the short length, a greater degree of bar warpage can be tolerated-this normally eliminates the cost of straightening operations.

"We cut our 12-foot bar stock into 4-foot lengths," says Mr. Queenen. "The bar feed needs spindle liners so they must be fitted to the size of bar that's being turned. The only bar preparation we do is deburring the cut ends. We keep a set of liners sized for our range of work. Change-over is a relatively simple thing, generally about five minutes to change bar sizes, because handling the short bar can be done by one person."

Another attractive feature, especially in the case of Matthews, is the automatic bar-loading capability of their system. The bar table or magazine allows a large number of bars to be loaded at one time.

Depending on the bar size and cutting cycle time, the machine will run unattended for up to 24 hours. Matthews capitalizes on this advantage to run a "lights out" night shift. The short bar design permits a very compact footprint that requires only 8 linear feet of floor space behind the machine. This length accommodates the bar pusher mechanism and the bar stock itself.

The design compares favorably to the 20 feet or so required by full-length bar feeders. This space-saving feature is a major issue with smaller shops where floor space is always at a premium.

Indeed, many shops buy these bar feeders because of the small footprint. To these shops' delight, there are other advantages after the system is installed. One surprise is the speed at which these units can operate.

Pedal To The Metal

Matthews, like many shops looking for bar feed capacity but lacking floor space, bought the short-length bar feed for its small footprint. However, because the bar is supported by a liner and the two turn together, this bar support design allows bars to rotate at maximum machine spindle speeds.

Many previous users of full-sized units have abandoned the bar feeding process because vibration at high speeds, particularly on long bars, forces the reduction of spindle speeds. As lathe spindle speeds have increased, bar feeding, including the hydrodynamic models of recent vintage, have not been able to keep pace.

On the short-bar version of the automatic bar feeder, the bar stock is fully supported in a spindle liner-tube-there is no speed-limiting friction element involved. The bar, spindle liner, and spindle all rotate as one balanced unit, which allows the lathe to turn at the maximum spindle speeds.

Matthews' Okuma turning center has a top spindle speed of 4200 rpm. That is very fast when there is a 12-foot-long piece of bar stock turning along with it. On the other hand, a 4-foot-long blank is much less intimidating.

"With the shorter bars, we end up with more remnants than a 12-foot feeder would," says Mr. Queenen. "However, the auto-load and storage feature overcomes that by storing enough bars to get us through a shift, and more, when needed. In addition, the faster turning speeds we can run with the short stock lowers our in-cut cycle time and gets us much better surface finish. The remnants can be used on our chucker, which, by the way, we still do some jobs on."

What's Next

By combining the savings from eliminating the prior chucking processing practice, and by instituting the "lights out" production method, Matthews has tripled the output of its lathes. So where does the company go from here?

Mr. Queenen has some ideas. "We successfully demonstrated that automation can be inexpensive and still be very effective. We'll continue to invest in CNC turning centers and machining centers that allow us to machine complete and as much as possible, unattended."

One area of improvement that Matthews is looking at, in addition to new machine tools, is automating the programming function. "Programming on the machine works fine," says Mr. Queenen, "but programs for some of the more complex parts-with turn/mill for example-could be better optimized off-line. It takes too much time on the machine tool to really tweak the program."

The idea at Matthews, and most metalcutting shops, is to get productivity and efficiency moving. Matthews has chosen smaller, incremental steps. What should be of interest to other shops looking to get cost down and efficiency up is that the same technology available to Matthews is available to any shop. Everyone has access to the same tools. Success comes in using these tools. n

For more information about SMW Systems Inc. call at (800) 423-4651.

For more information on Okuma's line of CNC turning centers, call (704) 588-7000.

Related Content

Prioritizing Workholding Density Versus Simplicity

Determining whether to use high-density fixtures or to simplify workholding requires a deeper look into the details of your parts and processes.

Read MoreRail Manufacturer Moves Full Steam Ahead with Safe, Efficient Workholding Solution

All World Machinery Supply paired a hydraulic power unit with remote operating capabilities in a custom workholding system for Ahaus Tool & Engineering.

Read MoreCustom Workholding Shaves Days From Medical Part Setup Times

Custom workholding enabled Resolve Surgical Technologies to place all sizes of one trauma part onto a single machine — and cut days from the setup times.

Read MoreMachining Vektek Hydraulic Swing Clamp Bodies Using Royal Products Collet Fixtures

A study in repeatable and flexible workholding by one OEM for another.

Read MoreRead Next

OEM Tour Video: Lean Manufacturing for Measurement and Metrology

How can a facility that requires manual work for some long-standing parts be made more efficient? Join us as we look inside The L. S. Starrett Company’s headquarters in Athol, Massachusetts, and see how this long-established OEM is updating its processes.

Read More