The Art and Science of Hand-Scraping Ways on CNC Machine Tools

Hand-scraping the mating surfaces of a CNC machine tool’s motion system offers myriad advantages.

Share

In an age of computer numerical controls and automated processes, hand scraping mated surfaces on a machine tool might seem a bit antiquated. Many OEMs have abandoned it, in fact, pointing to the extra time and effort the operation requires. Some still stand by its value, however, claiming that the craftsmanship involved—and the benefits it provides—cannot be duplicated mechanically. So what is hand scraping, and is it a feature that buyers should seek out when considering the attributes of a new machine tool?

Hand scraping is a manual process of truing and providing texture to mated surfaces in a machine tool. It is most often performed using a flat scraper, which is a hand tool with a flat-edged tip similar to a wood-carving tool. The tip of the scraper is generally an inch wide or smaller, matching the width of the metal shaft—which can be of various lengths—for rigidity. The person performing the operation holds the tip of the scraper firmly against the surface to be worked with one hand while grasping the tool handle with the other, thrusting the tool against the surface with powerful strokes using the body’s weight in order to create a pattern. Other tools used for hand scraping include a three-corner scraper, which is often used to deburr holes, and a curved scraper that can treat the surface of bush bearings.

Understanding Hand Scraping

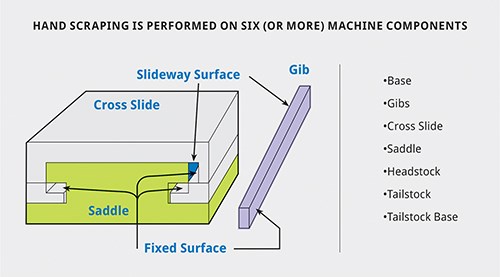

According to Okuma America Corporation—a longtime advocate for the process—the main reasons for hand scraping mated surfaces have to do with oil retention, stability and accuracy. Once the two castings have been joined, the upper piece is coated with engineer’s blue—the pigment Prussian blue in an oil base—and rested atop the way on which it will ride during operation. The resulting imprint reveals areas of contact, allowing the hand scraper to true the surfaces so that they are properly mated but also to create pockets or slight depressions in which oil can pool while its surface tension is retained. This enables a smooth, gliding movement and helps avoid the “slips and starts” caused by contact between perfectly flat surfaces from which lubricants tend to be squeezed. This causes the metal surfaces in contact with one another to grab and seize. The ideal, for most machine tool slideways, is to create approximately eight points of contact between the mated surfaces per square inch, providing flatness and stability and preventing rocking. Typically about six components within an average machine tool will have surfaces to which hand scraping can be applied.

The Difference Between Scraping and Machining

So, isn’t it possible for this manual surface-finishing procedure to be performed by a machine? Some OEMs do just that, machining oil grooves into flat surfaces, while others have transitioned completely to precision linear rails that can be mounted with screws and replaced when they become worn. There are also power tools that can be used to produce an oil-trapping surface texture. The obvious questions involve how machined channels affect surface integrity and whether accuracy is compromised toward the end of a linear rail’s service life. Lapping is sometimes used, but it tends to address the entire surface without creating the high contact points so useful in achieving stability, and it is not ideally suited for creating long, flat surfaces.

Probably the most convincing reason for seeking out hand-scraped mated surfaces in new machine tools involves the fact that the castings used in these applications are, by their very nature, somewhat irregular in their geometry. In addition, the grinding and machining methods used to simulate hand scraping can introduce contracting, flexing and expansion of material—and, later, distortion. So the logical conclusion here may be that the art of hand scraping still has a place in the science of building accurate, reliable, long-lasting machine tools.

Related Content

Shop “Dims the Lights” With Pallets and More

Adding pallet systems brought Mach Machine success and additional productivity. The shop has since furthered its automation goals while adding new capabilities.

Read MoreSW North America Open House Showcases Advanced Machining Solutions

SW North America hosts its 2025 Open House at its Michigan headquarters, featuring live demonstrations of the BA 322i and BA Space3 machining centers with a focus on medical and aerospace applications.

Read MoreNavigating Large-Scale CNC Machining: Suburban Tool’s Niche Strategy to Stay Competitive

Facing increasing competition from lower-cost imports, Suburban Tool made a move toward large-scale, in-house machining. By identifying a niche in large, precision angle plates and tombstones, the company has strengthened its ability to control quality and protect its reputation.

Read MoreDMG MORI HMCs Reduce Energy Consumption

DMG Mori Co. Ltd. introduces the NHX 4000 and NHX 5000 4th Generation, designed for high-speed, sustainable production with reduced cycle times and energy consumption.

Read MoreRead Next

Secrets to the Art of Hand Scraping

Hand scraping of mating surfaces on a machine tool enables the surfaces to be flatter, more accurately aligned, longer wearing and freer to glide across one another. No automated or mechanical operation can match these benefits. Machine builder Okuma explains how this seeming paradox is true.

Read MoreOEM Tour Video: Lean Manufacturing for Measurement and Metrology

How can a facility that requires manual work for some long-standing parts be made more efficient? Join us as we look inside The L. S. Starrett Company’s headquarters in Athol, Massachusetts, and see how this long-established OEM is updating its processes.

Read More