The Extrusion Option

For the right parts, this choice might be surprisingly cost-effective. A drum pedal maker controlled cost by starting some machined components as extruded blanks instead of solid blocks.

Share

Do drummers appreciate machining? Some do. DW Drums, the manufacturer producing drums and drum accessories in Oxnard, California, is speaking to the drummers who do appreciate machining with the branding of one of its products. The company’s new, advanced family of foot pedals is the “MDD” line, for Machined Direct Drive. Machining was essential to realizing the design improvements that this line delivers, so machining deserves to be part of the product name. However, even after the company switched from casting to machining of billet aluminum for the production of this pedal’s components, there was still one more important step to take.

Rich Sikra is DW Drums’ vice president of manufacturing. That position at this company makes him not just a producer, but also a designer. A drummer himself, Mr. Sikra applies his knowledge of manufacturing in cooperation with other DW designers to find ways to make components easier to produce, and also to leverage the full capabilities of the company’s production resources to create products that improve the experience of the drummer. DW invests in in-house production so it can continue to realize the innovation—the tinkering, really—that comes from design and manufacturing team members interacting every day.

In fact, Mr. Sikra himself was part of the investment in in-house production. A former machining business owner, he used to be a supplier to DW. The company asked to buy his shop to obtain full use of his equipment, staff and knowledge. Mr. Sikra has been an employee ever since, and the development of the MDD pedal came as a direct result of having machining capability under DW’s own roof.

One of the pedal features of which he is particularly proud is the spring system, he says. He helped develop this. On other pedals, the mechanism for manually changing spring tension is awkward enough that the pedal has to be pulled away from the drum to make the adjustment. On the MDD, the seated drummer can adjust the spring tension just by reaching down and making a turn with one hand. This is because using machined components instead of castings allowed the company to conceive of an entirely different configuration of the spring assembly. Now that the design is proven, Mr. Sikra is still working on it by seeking to make the manufacturing processes for the pedal’s components continually more cost-efficient.

Initially, much of the cost of these components came from metal removal. That would seem to stand to reason for a product identified for its machining. But did there have to be so much machining? Seeking an option for beginning with workpieces that were nearer to net shape than rectangular blocks, Mr. Sikra found aluminum extrusion—and he also found a surprise. Extrusion dies for aluminum are often cheap, he discovered. For a part shape that is well-suited to this process, the die might be only hundreds of dollars, which is an easy cost to recapture from the savings in time, tools and material that come from reducing machining. Now, 10 of the 20 machined parts in the MDD pedal begin as extruded blanks.

Part of the reason he had overlooked extrusion in the past is because he had been accustomed to casting, he says. In casting, the tooling cost is comparatively high, and he had assumed that something like the same economics of tooling applied to extrusion.

“I wish I had known,” he says. “Back when I was a shop owner, there are jobs I lost that I probably would have won if I had better understood extrusion’s pricing.”

Corners and Walls

Discoveries like this one are common, says Mike Thrush, a sales manager with Paramount Extrusions Co. in Paramount, California, one of DW Drums’ aluminum extrusion suppliers. Mr. Thrush says there are plenty of aluminum parts being machined today in which more cost than necessary is going into reducing metal to chips.

Paramount accepts small orders, and for DW, this was key. Finding extruders willing to take orders matching DW’s small part quantities entailed some searching, Mr. Sikra says. Paramount operates small presses and specializes in smaller, more complex extruded forms. Orders for extrusion are measured by weight, and this extruder is distinctive for being willing to run jobs so small that the total yield of usable material is only about 23 pounds. Even DW’s orders are generally much larger than this.

The extrusion process involves forcing material through a die. Extruded parts thus are essentially 2-1/2 D-pieces. Softer metals can be extruded, including copper, brass and (DW’s interest) aluminum. Heated billet is shaped by the die into a length of stock with a profile matching the die’s cavity, and this extruded stock can then be sawed into pieces to create blanks ready for machining.

To help machine shops identify where extrusion makes sense, Mr. Thrush answered some questions I put to him:

1. What factors make for an effective extrusion design?

Look for parts that are symmetrical, and have rounded shapes or features, as well as radiused corners and consistent wall thicknesses, he says. These details all indicate a part that might be a good candidate for extrusion.

2. What are the factors to watch out for?

Several factors might make extrusion difficult, he says. They include:

• Sharp corners, particularly corners with radii smaller than 0.015 inch.

• Wall thickness that varies, meaning walls that transition from thin to thick.

• Deep channels, particularly channels with a depth-to-opening ratio greater than 3:1.

None of these features rules out extrusion, but the presence of any of them is liable to increase cost.

3. Does the extruded part have to be entirely solid?

No, the extrusion can have one or more profiled cavities through it. The profile of this cavity is formed with an additional tool, a piece holding a form like an island just past the cavity of the primary die. However, features such as this add difficulty and cost, and a form with many hollow features is liable to be a poor choice for extrusion.

4. What about thin walls?

Paramount has extruded parts with walls as thin as 0.020 inch, he says. Different profiles respond differently to extrusion, so not every wall so thin is attainable. A common compromise for shops wanting parts with very thin walls is to extrude 0.040- or 0.050-inch walls and use light machining passes to get them to their final size.

5. What order sizes are typical?

Extruders with larger presses (capable of producing bigger parts than Paramount can) commonly have minimum order limits of 1,000 pounds or higher. Paramount essentially has no minimum—the 23 pounds mentioned earlier is the yield of a single piece of billet. Many of the company’s customers place orders of 300 to 500 pounds.

6. Name a part that proved to be a great candidate for extrusion.

A Picatinny rail, he says. This is a firearm component, a long bracket with a T-like profile enabling sites, bayonets and other accessories to be affixed to a rifle. Because the part is essentially a long, straight, profiled member (with cross slots later added through milling), the part proved ideal for extrusion. The switch to extrusion saved considerable machining time for a company that used to cut these rails out of barstock.

The $600 Die

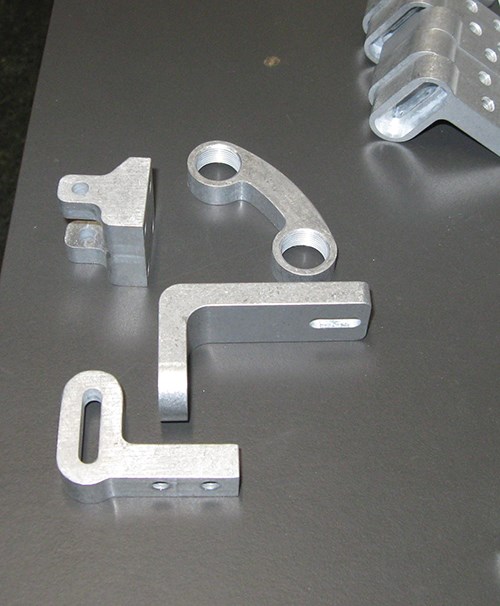

In the collection of parts seen in the photo at the start of this article, the L-shaped part is an example of the kind of component that makes Mr. Sikra marvel that he didn’t turn to extrusion long ago. For a part such as this to be machined from a solid block, more than half the block’s mass has to be machined away, generating cost in terms of machine time, tool wear and scrap metal. By contrast, this form is easy to extrude. Plus, extrusion and sawing together produce a sufficiently accurate blank that machining may be needed only for the details, not the overall form. The die for a part resembling the L-shaped piece seen here was just $600, which DW quickly recouped from the machining savings.

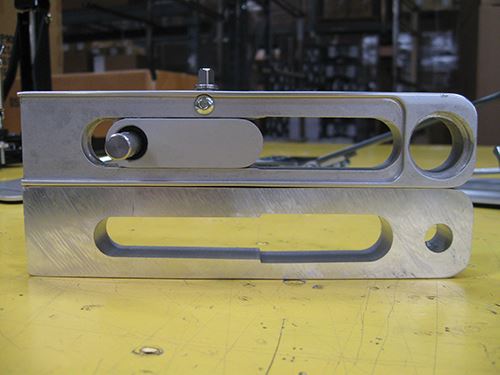

Meanwhile, the rectangular part seen in the photo on this page (the same part Mr. Sikra is holding in an earlier photo) is an example of a more challenging extrusion. “As soon as you put a hole in the part, the price of extrusion goes up, because that’s another tool,” he says. The tooling for this part was $7,000, yet even this was cost-effective. Machining this piece from solid—that is, both machining it to size and machining the internal cavity—entailed enough handlings and metal removal that extrusion was cheaper in this case as well.

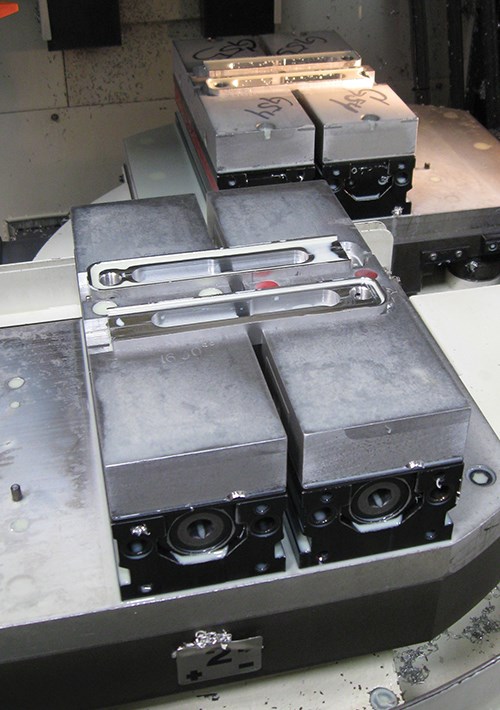

For those contemplating using extruded parts, Mr. Sikra points out that the die is not the only needed tooling. Workholding is an issue, too, he says. The blanks generally need custom fixturing. In his shop, the extruded form generally requires soft jaws, and perhaps a little imagination, in order to suitably clamp the piece and hold it for whatever machining it still requires.

In fact, even an extruded part intended to be square might have something of a profiled form. That was the case with the rectangular part previously mentioned. Extrusion for this part results in one of the part’s sides not being precisely straight, but bowing slightly inward. Because this is a visible part and the MDD pedal has to look precise, Mr. Sikra was initially concerned. Yet on further examination, he learned that the flatness error is too slight to impair the pedal’s functionality, and—just as significant—the error is consistent from piece to piece and batch to batch.

So he measured this error from point to point along the length of the extrusion. Using these measurements, he added the same error into the tool path used to finish mill the pocket along the length of this part. As a result, even though the extrusion is not precisely straight, the bowing does not detract from the attractive look of the machined components. The long rectangular member looks perfectly straight, he says, though this is an illusion. The pocket following the part’s length is simply bowed to the same

tiny extent.

Related Content

Machining with a Mission

Learn how veteran-owned shop Win-Tech not only excels in aerospace and defense manufacturing with CMMC level two compliance, but also transforms lives by hiring veterans and encouraging students to explore manufacturing.

Read MoreRoughing First: New Strategies for Blisk Machining

Aerospace shops looking to cut cycle time and tool wear on integrally bladed rotors often focus on finishing. But rethinking the roughing stage can increase how much material can be safely removed while accelerating throughput.

Read MoreHow to Meet Aerospace’s Material Challenges and More at IMTS

Succeeding in aerospace manufacturing requires high-performing processes paired with high-performance machine tools. IMTS can help you find both.

Read MoreHow Precision Blanks Help This Aerospace Shop Build Better Parts

Internal stress in thin metal parts can lead to warped components and scrapped work. Matrix Machine found a better way by sourcing precision-ground blanks from TCI Precision Metals. Here’s how that decision freed up capacity and made critical parts more predictable.

Read MoreRead Next

OEM Tour Video: Lean Manufacturing for Measurement and Metrology

How can a facility that requires manual work for some long-standing parts be made more efficient? Join us as we look inside The L. S. Starrett Company’s headquarters in Athol, Massachusetts, and see how this long-established OEM is updating its processes.

Read More

.png;maxWidth=300;quality=90)