Just Enough Automation

Automated gantry loaders helped this shop make the transition from job shop to product line manufacturer.

Share

Oil wells use lots of pumps. At almost every step in drilling or operating an oil well, pumps are needed to get various materials in and out of the ground. All of these pumps require numerous valves to control the flow of these materials, many of which are highly abrasive or corrosive. As a result, these valves and the seats they mate with wear out and need to be replaced. Novatech Corporation is in the business of manufacturing these replacement components.

This 19-person shop in Dallas, Texas, was making many of these parts before it became a pump valve company with its own product line. Novatech started out as a job shop, with precision turning as one of its specialties.

Getting Involved With Valves

Because pumps come in many sizes and types requiring many different sizes of valves and seats to match each pumps capacity, pump manufacturers have to supply a wide variety of replacement parts. These companies were looking for job shops that could produce the pump valve components that need to be replaced frequently. These parts consist largely of axisymmetric shapes, so lathe work is a main part of their production. Because Novatech was experienced at turning, the shop was a good choice for machining these valves.

The company eventually expanded to become a job shop supplier for several pump manufacturers. It began making components for both "mud" pumps used in oil well drilling along with components for well service pumps used to keep an oil well operating. In the meantime, the company continued to do other job shop work, such as defense-related contracts.

The 1990s saw many changes in the oilfield industry. There was widespread consolidation among the oilfield equipment dealers and distributors, leaving many of the independent equipment sellers with gaps in their valve product lines. A number of these sellers turned to Novatech to fill the gap.

Mr. Pitzer realized that his shop could manufacture the most popular valve types very efficiently and be highly responsive to the independent sellers serving oil wells in the field. Novatech was in the right position to make and market its own line of pump valves. Yet Mr. Pitzer didn't want the shop to lose its heart and soul of a job shop. The shop would need all of its job shop flexibility, creativity and constant focus on efficiency to succeed in its valve business.

"From the start of this transition, we knew that automation would be a key part of our emerging production strategy," Mr. Pitzer recalls. "But not too much automation—just enough."

The Right Kind Of Growth

The more Mr. Pitzer analyzed his prospects as a product line manufacturer, the more he was convinced that automation was essential. Two factors were especially prominent in his thinking about how the business could grow. One, he knew that increased production would be required to support higher sales. However, simply hiring more people or buying more machines wouldn't be effective if these resources couldn't be used as efficiently as possible. That would make the company bigger, but not necessarily more profitable.

Two, he needed to preserve as much flexibility as possible. Given the wide variety of valves and seats that would comprise Novatech's emerging product line, producing small batches (200 to 300 pieces) would best meet customer orders without creating excess inventory. More important, batches in this range matched the number of pieces that the heat treater could carburize at one time. At this batch size, the heat treater could provide the best turnaround time and lowest cost per piece.

At the time, the valves and seats were being machined on the shop's CNC lathes, which were manually loaded and unloaded. It was clear that this approach was inadequate to handle the optimal batch sizes that were a key part of the production strategy. Several factors were holding back the productivity of these machines. One was operator fatigue. The valve parts are heavy, ranging from 7 to 17 pounds each. Cycle times were around 2 to 3 minutes per part. That meant a lot of lifting and stretching for the operator during an entire shift. "At most, we could expect an operator to do 100 to 150 parts per shift, depending on the weight of the part," says Mr. Pitzer. "We needed to double that output per operator and make better use of their abilities."

Another factor was downtime for part inspection, chip removal, indexing insert edges and other activities that interrupted or delayed chip cutting. Finally, these machines had outdated controls and drive systems.

Mr. Pitzer was determined to move ahead with up-to-date turning technology. He was aware that automated gantry loaders might be the right kind of automation to complement new machine tools, so he investigated this type of equipment. It seemed to make sense for his application. "I could see that these systems could keep a machine tool running part after part while the operator tended to other duties off-line," Mr. Pitzer recalls. The flexibility of the loaders also appealed to him. Changeover from batch to batch would not be an issue.

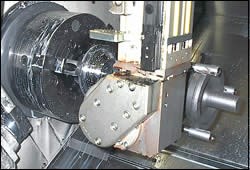

Mr. Pitzer approached his local machinery dealer with this plan. They agreed on a pair of Crown turning centers from Okuma (Charlotte, North Carolina), each equipped with TCL automatic gantry loaders from Wes-Tech Automation Systems (Buffalo Grove, Illinois).

In 2001, these machines were installed as a cell with the two CNC turning centers facing each other. A year and a half later, the shop installed a second cell on the opposite side of the main aisle in the 16,000-square-foot facility. This cell consisted of two Okuma Captain L47M CNC turning centers facing each other. These larger machines were equipped with Wes-Tech gantry loaders almost identical to those on the original cell.

According to Mr. Pitzer, the gantry loaders represented about one half of the total investment in each cell, but they boosted output of the machines an average of 50 percent, even with cycle times remaining fairly constant. In some cases, the improvement was even better. "With manual loading, we were producing 180 of our best-selling valves on two machines with two operators per day," Mr. Pitzer reports. "On the automated cell, we can produce 300 per day. That's two machines with only one operator."

The Loaders At Work

The automatic gantry systems consist of a chain-driven carrousel with 25 stations, a vertical arm that raises and lowers the gripper, and a crossbeam that carries the arm back and forth between the machine and the carrousel. The double-sided gripper is designed to grasp and manipulate the workpiece. The construction of these systems is modular, allowing the loaders at Novatech to be configured for the specific machine tools in its cells. Because the machines face each other, the loaders are configured in right- and left-handed versions.

The operator puts raw castings on the carrousel and removes finished pieces, placing them in a bin or transferring them to the carrousel on the opposite machine. No special fixtures are needed on the carrousel. Valve seats are simply positioned within circular lines on the rubber pads covering each pallet station, whereas valves with stems are placed stem down on simple, tubular risers.

When actuated by a signal from the gantry system's controller, the arm descends into the machine and positions the gripper fingers around the finished part in the chuck. After grasping the part and retracting it from the chuck, the gripper rotates and delivers an unfinished part held in the other side of the gripper. A built-in pusher ensures positive registration of the new part in the chuck. After this part is secured in the chuck, the arm lifts the gripper out of the machine and travels horizontally on the crossbeam to the carrousel. The gripper swivels so that the finished part can be deposited on the carrousel. Afterward, the gripper is ready to pick up an unfinished part and start over.

The gantry loader is fully enclosed by fencing, with gates interlocking with the control for safety. Other safety features are in place to avoid hazards to the turning center, cutting tools, workpieces and the operator.

As the gantry loads and unloads the lathe automatically, the operator attends to such chores as keeping the carrousel stocked, inspecting sample workpieces, changing inserts when preset edge life is reached, running the chip conveyor to keep the machine bed clear and so on.

Changeover from one type of part to another in the same family usually requires changing only the part program. To change from valves to seats takes approximately 90 minutes. The gantry loader can be programmed in the "step through" teach mode, which requires only new end points to be taught. The hand-held "teach" pendant lets the operator "jog" the loader to the desired end points.

Lessons Learned

After operating the automated cells for 3 years, Mr. Pitzer has some interesting insights and observations about the effectiveness of this production strategy. These thoughts are summarized here.

- Simplicity is a key value in automation. It makes automation easy to understand and the benefits easy to see. Simplicity keeps costs down. "Automatic loading gives us the best cost-to-benefit ratio," Mr. Pitzer says. "More automation would give us diminishing returns." On a practical level, simplicity contributes to flexibility. Novatech's gantry loaders do not require customized grippers or pallet fixtures. Changeover is quick. There is less chance of setup error.

- Automation does not necessarily mean untended operation. For Novatech, the value of automation is in enhancing the productivity of the machine and the operator. The shop does not operate the cells in the untended mode. The goal for automation is to match the output of operator-tended shifts with production requirements. "We could run one more carrousel full of parts at the end of the day if we wanted to, but that hasn't been necessary," Mr. Pitzer says. The automatic loaders allow the operator to act as cell supervisor, taking care of duties without interrupting production. Many of these activities could be automated, but at considerable expense and complexity. The efficiency of the machines would not increase significantly from additional automation, notes Mr. Pitzer. "So why do it?" he asks.

- With any automation, attention to details is important.Chip control is a good example. Novatech experimented with various turning insert grades and styles to find those that provided the most reliable chipbreaking function. Avoiding long, stringy chips is critical because resulting "bird's nests" can interfere with the gripper or the chuck. Details about the chuck jaws proved to be important. The shop installed the more expensive one-piece quick-change chuck jaws because they had fewer places for chips to get caught on. For certain parts, the corresponding chuck jaws have been modified for better flow of compressed air during the chip clearing cycle. Coolant-fed toolholders are also used wherever possible. Coolant gets to the right place even if the regular coolant nozzles are not positioned optimally. Finally, attention to details requires good communication. For example, all setup notes and reminders are stored as text lines in the part program. That way, the operator does not need paperwork on a daily basis.

- Operations on an automated cell must be balanced carefully. In some cases, parts can be processed on the cells in two operations, one on each machine. Typically, valve seats are processed this way. One side is completed on one machine and then transferred to the other machine to complete the other side. This approach is effective because the two operations are close in cycle time. Valves, in contrast, are usually processed in two operations, but machining the valve body requires a considerably longer cycle time than the stem side. Because the two operations are so unbalanced, both machines in the cell are assigned to turn the flow side. The stem side is then machined on a turning center outside the cell.

- Automation is only one part of the productivity picture. Novatech continually looks for every opportunity to reduce cycle time and production costs. For example, the company originally used one forging to produce three different valves. This approach reduced the cost of the forge tooling. As quantities increased, it became more cost effective to design separate forgings for each valve so that the forging was nearer to net shape. The new forgings used less material and required less machining. These savings more than compensated for the cost of producing new tooling.

Partnering with the heat treater has also resulted in savings. With the promise of substantial business from Novatech, the heat treater invested in a larger capacity furnace. This allows Novatech to flex batch sizes more liberally without creating a bottleneck.

Novatech also studies product design for ways to improve product quality or reduce costs. For example, many valve bodies require a urethane seal around the OD. The company has developed and patented a technique for molding this seal directly to the valve body, streamlining the process of valve assembly.

An Automated Grinder Is Next

According to Mr. Pitzer, a new grinder for grinding tapers on valve sets after heat treating will be delivered in the second quarter of 2004. "Our plans for this grinder include automated gantry loading as part of the equation," he says. "We wouldn't consider acquiring this machine without the productivity offered by the automation."

The grinder is scheduled to arrive about 2 weeks before the gantry system comes in. The time in between gives the shop a chance to prove out the grinding process. Any last-minute considerations that might affect automated operation can be settled before they interfere with setup of the gantry loader.

Mr. Pitzer believes that, once again, this level of automation will prove to be just enough for the optimal combination of productivity and flexibility.

Related Content

3 Ways Artificial Intelligence Will Revolutionize Machine Shops

AI will become a tool to increase productivity in the same way that robotics has.

Read More5 Stages of a Closed-Loop CNC Machining Cell

Controlling variability in a closed-loop manufacturing process requires inspection data collected before, during and immediately after machining — and a means to act on that data in real time. Here’s one system that accomplishes this.

Read MoreSetting Up the Building Blocks for a Digital Factory

Woodward Inc. spent over a year developing an API to connect machines to its digital factory. Caron Engineering’s MiConnect has cut most of this process while also granting the shop greater access to machine information.

Read MoreAerospace Shop Thrives with Five-Axis, AI and a New ERP

Within three years, MSP Manufacturing has grown from only having three-axis mills to being five-axis capable with cobots, AI-powered programming and an overhauled ERP. What kind of benefits do these capabilities bring? Find out in our coverage of MSP Manufacturing.

Read MoreRead Next

OEM Tour Video: Lean Manufacturing for Measurement and Metrology

How can a facility that requires manual work for some long-standing parts be made more efficient? Join us as we look inside The L. S. Starrett Company’s headquarters in Athol, Massachusetts, and see how this long-established OEM is updating its processes.

Read More