Training Time

The graying of skilled metalworkers adds impetus to the growth of standardized training programs.

Share

During a machine shop tour, the supervisor invariably stops along the way to introduce the visitor to at least one veteran machinist who represents the backbone of the shop’s workforce. As he stands in front of a knee mill, the man’s face is a living testament to the patience, determination and keen powers of observation required in the metalworking trade. For 25 years, “Charlie” has been this shop’s security blanket—making difficult tasks seem easy, and solving problems that sometimes seemed intractable.

More frequently these days, however, Charlie talks about his lakeside cottage, fishing boat and retirement plans. When the supervisor strolls through the shop nowadays, he often wonders who on earth will take Charlie’s place.

With the retirements of many highly skilled machinists who entered the metalworking trade in the decade following World War II, this scenario has played out in thousands of machine shops across the United States. As the 1990s began, the declining number of skilled workers emerged as a serious threat to the industry, despite the mitigating effect of more widespread and advanced technology.

At the same time that formally trained metalworkers seemed to become an endangered species, it also became increasingly difficult for shop owners to verify the skill levels of new and prospective employees. In the absence of clear standards, how could an applicant’s qualifications be measured? For example, if a job applicant claims to be a “machinist,” how is this term defined? What kind of training and experience does the person have? With which types of machinery and materials is the person competent, and to what degree of accuracy?

Historical Background

For several years, metalworking companies have described the impact of a growing skills gap to trade associations, labor unions and others. This feedback became the initial impetus to organize and standardize training programs. In 1995, the National Institute for Metalworking Skills (NIMS) was formed to extend standardized training and education nationwide. In addition to promulgating, developing and maintaining skill standards, NIMS documents the skills of individuals and awards credentials. The organization also promotes, assists and certifies various training programs.

The original initiative to develop these standards was taken in 1993, when the U.S. Departments of Education and Labor provided cost-sharing grants to establish voluntary skill standards in key American industries. This initiative was based on the National Skill Standards Act of 1994, whereby Congress created the National Skills Standards Board (NSSB) to enhance the ability of America’s labor force to compete in the global marketplace. At the same time, the National Tooling & Machining Association (NTMA) partnered with the Council of Great Lakes Governors to gain funding for establishing metalworking standards.

In 1997, the Manufacturing Skills Standards Committee (MSSC) was created as the result of an NSSB grant. The MSSC is a coalition of businesses, labor unions, trade associations, professional organizations, educators and other public interest groups from across the manufacturing sector.

Setting The Standards

Many people in the industry believe that metalworking has been given the short shrift in educational programs, thereby discouraging young people who might otherwise enter the trade. Early exposure and training, however, are precisely what NIMS programs provide. Training programs eligible for NIMS certification include those offered by educational organizations (vocational/technical schools and public high schools), company-based programs or inter-firm programs conducted by collaborating companies, trade associations or labor organizations.

NIMS has expanded on the pioneering efforts of certain private companies and NTMA to develop metalworking skill standards. NTMA had previously established three basic performance levels for training programs. Level I comprises skills that would be expected of an operator with one year’s experience as an apprentice. These skills include basic competence with machine tools and accessories, elementary shop math and inspection procedures. Level II comprises more complex skills and theory, including CNC principles, more sophisticated equipment, measurement and math. Level III training equates to journeyman skills, including competency with a wide range of tools, machining tasks, job layouts and the ability to work with minimal supervision.

NIMS certifies training programs that provide instruction at Levels I and II. Although NIMS does not certify training programs that provide Level III instruction, it does offer credentialing opportunities for individuals trained to this skill level. The activities of NIMS are financed through tax-deductible contributions from industry organizations and member companies, technical education grants from states and the sale of NIMS products. The principal metalworking organizations that support NIMS include the American Machine Tool Distributors Association (AMTDA), the Association For Manufacturing Technology (AMT), the NTMA, the Precision Machined Products Association (PMPA), the Precision Metalforming Association (PMA) and the Tooling and Manufacturing Association (TMA). Additionally, NIMS training is supported by the AFL-CIO as part of its various worker training programs.

The NIMS credentialing program comprises a set of standards that were written and validated by the metalworking industry. The NIMS Machining Level I Credentialing Program is based on Duties and Standards for Machining Skills—Level I, developed jointly by NTMA and TMA. Assessment standards for NIMS training levels are identical throughout the nation, thus making worker credentials portable.

In the Machining Level I training program, eight different credentials may be earned, including the following:

- Measurement, materials and safety

- Job planning, benchwork and layout

- Milling

- Drill-press operation

- Surface grinding

- Turning between centers

- Turning/chucking

- Credential of Special Merit (awarded for successful completion of all Level I skills).

Putting Skills To The Test

A person who wants to earn NIMS credentials must be registered by a sponsor (usually the person’s instructor, supervisor or employer) and pay a one-time registration fee. The registrant’s sponsor is responsible for furnishing all paperwork necessary to document that the trainee’s NIMS requirements have been met.

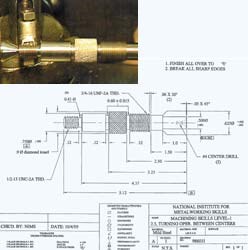

After registration, the person must machine a workpiece in one or more of the program’s skill modules according to specifications shown on a corresponding part print (Figure 1). The machined workpiece must then be evaluated by a Met-Tec review committee. These committees are composed of qualified industry representatives who volunteer their services to evaluate trainee competency. For a candidate to receive a passing grade, all dimensions of the test workpiece must be within allowable tolerances. If the workpiece conforms to specifications, members of the Met-Tec sign a performance affidavit that is submitted to NIMS with the registrant’s file.

After receiving this information, NIMS schedules the written portion of its credentialing exam and notifies the registrant of the exam date. Written exams cover theory and some additional knowledge required for job duties related to the registrant’s performance tests. These exams have been composed by workers and supervisors employed by machining companies, and grading is pass/fail according to a predetermined minimum score. A registrant may take up to three credentialing exams on a single exam date. If the person fails, two additional opportunities are provided to take each exam.

Written exams are organized in reference to specific topics that are weighted according to their relative importance (Figure 2). Within 5 weeks after the exam date, NIMS notifies the sponsor of a successful candidate and awards the appropriate credentials. Credentials are effective for up to 5 years from the date of award.

Getting With The Program

Sipco Molding Technologies (Meadville, Pennsylvania) is a tool and die shop that has been a leading proponent of the NIMS training program since its beginning. Sipco specializes in building precision plastic injection molds for the electronics, automotive and consumer products industries. Although the firm has maintained an internal training program since it was founded in 1959, the subjective standards it previously used to evaluate competency didn’t measure individual skill levels with precision. After it began the NIMS program in 1998, however, Sipco was able to establish objective, universally recognized skill standards for its shop personnel.

Sipco’s co-owner, Larry Sippy, is a strong supporter of the NIMS training program. Mr. Sippy also served on the NTMA Apprentice Committee and volunteered his company to be a pilot testing site for NIMS written exams. After this early experience, Sipco began to integrate NIMS training into its apprenticeship program, requiring all apprentices and trainees to complete the testing. In January 2000, the company was certified as a NIMS training site.

According to human resources director Tamara Adams, Sipco promotes NIMS training by running advertisements in the local newspaper, as well as by encouraging the local vocational school to have students tested. For young people interested in pursuing a trade, the “learn as you earn” opportunity of metalworking training has strong appeal. Completion of NIMS training in high school or vocational school also represents an important advantage in terms of the person’s starting pay scale.

Sipco has already integrated NIMS training into its wage scale (Figure 3). For example, a new employee who has earned a Level I credential in either milling or grinding is eligible to receive 50 cents per hour more than a new employee with no training or experience. At the high end of the scale, new employees who have earned Level II credentials in both milling and grinding receive $3 above the shop’s basic hourly starting rate.

When machine shops make NIMS training an avenue leading to higher starting wages, this creates strong incentives for students to obtain additional training and credentials. Sipco has found that making these incentives part of its wage scale has encouraged development of a competent workforce. In effect, this extends a shop’s apprenticeship program beyond its walls and into classrooms.

Sipco works closely with Precision Manufacturing Institute (PMI), a local training facility that was recently certified as a NIMS training site. To support this training, Sipco has established a local Met-Tec committee that includes PMI, a metrology company and some tool shops.

While meeting the critical need for properly trained and credentialed metalworkers, machine shops also derive some additional benefits from NIMS programs. According to Ms. Adams, integrating NIMS training into Sipco’s hiring and promotion processes has also helped the company with its ISO certification. Because many of the shop’s processes are labor-intensive, ISO auditors request documentation that verifies workers’ skills. Sipco now requires all new shop employees to complete NIMS testing, whether or not they are registered apprentices. This enables the company to evaluate an individual’s skill level and identify areas in which the person needs additional training or experience.

Making The Grade

Programs that seek NIMS certification must first provide students with access to machine tools and the necessary tooling to meet performance requirements. Additionally, all training equipment and tooling must be comparable to that found in the workplace, and proper safety and maintenance procedures must be observed. An advisory committee must also be established for each program. For educational or inter-firm programs, this committee should comprise representatives of at least five different metalworking companies, and the committee must have at least two working meetings per year from which official minutes are recorded. In company-based programs, an additional requirement is that the advisory committee include members of both management and workers.

To obtain Level I certification for the maximum 5-year term, a program must sponsor at least one group of students or trainees and test them in at least one of the NIMS Level I exams. A minimum passing rate of 25 percent for all exams attempted is also required for certification.

Level II certification programs must sponsor at least one group of students or trainees in each of the Level II training modules for which the program seeks certification. To earn 5-year certification, the program must achieve a minimum passing rate of 50 percent on all tests. For initial certification of a training program, NIMS will waive the requirement that all instructors hold NIMS credentials, but instructors are required to earn these credentials within 18 months after their program is certified.

According to Ms. Adams, however, companies who want to certify their training programs should not hesitate due to fears of red tape. “We didn’t have to invent anything to make this happen,” she says. “We simply organized the documentation in a single binder to support our claims on the self-study.” (The “self-study” is a self-rating form that the training program submits for NIMS certification.) According to Ms. Adams, backup documentation for claims made on the self-study form includes items such as employee handbooks, equipment inventories and summaries of trainers’ qualifications. Because this is information that all shops should have readily available, the certification process does not require a substantial amount of additional paperwork.

Public/Private Partnerships

With the increasing emphasis on practicality in public school curricula, NIMS programs have recently received a welcome boost from certain public school systems.

The North Carolina Department of Public Instruction, the governing body for the state’s public schools, has integrated NIMS-certified training into its Trade and Industrial Education program. Under this program, Metals Manufacturing Technology courses are now offered in grades 9 through 12.

Pennsylvania’s Director of Vocational Education, John Foster, announced recently that his state’s goal is to certify 80 percent of its vocational programs, as well as to have 80 percent of all students in metalworking programs earn NIMS credentials. Meanwhile, the Cleveland Municipal School District and local industry representatives recently signed the Cleveland Metalworking Partnership Agreement to expand metalworking training in the city’s public schools.

Under this agreement, the school district pledges to have all students in vocational programs complete NIMS testing. Additionally, the Cleveland school district has committed to the same 80-percent rate of credentialed students as Pennsylvania. In return, participants from Cleveland’s metalworking industry will provide technical assistance to the schools, as well as placement and apprenticeship opportunities. These efforts are being directed through the Cleveland chapters of NTMA, PMA and PMPA.

The modest dimensions of current training programs underscore the crucial role of strong industry participation. At present, NIMS-certified programs are available in only 14 states, with Ohio and Pennsylvania accounting for the lion’s share of training opportunities. Without considerable support from key members of the metalworking industry, however, the NIMS program would still be sitting on the launching pad. Many of these people have donated generous amounts of their precious time to ensure that tomorrow’s machine shops will have an adequate talent pool. By utilizing a nationwide network of educational and training programs already in place, NIMS training represents an efficient solution to the persistent skills shortage. Indeed, this training approach reflects the best traditions of an industry strongly rooted in practicality. As these programs expand and attract greater industry participation, a future that once seemed murky begins to appear brighter.

Related Content

Finding the Right Tools for a Turning Shop

Xcelicut is a startup shop that has grown thanks to the right machines, cutting tools, grants and other resources.

Read MorePreserve the Craft of Manufacturing as Technology Advances

As the industry continues to move toward a digital future, be sure to reinforce the core fundamentals right alongside it.

Read MoreHow I Made It: Montez King

From high schooler pushing a broom on a shop floor to executive director of the National Institute of Metalworking Standards (NIMS), a series of bold decisions have shaped Montez King’s career path.

Read MoreInside Machineosaurus: Unique Job Shop with Dinosaur-Named CNC Machines, Four-Day Workweek & High-Precision Machining

Take a tour of Machineosaurus, a Massachusetts machine shop where every CNC machine is named after a dinosaur!

Read More

.png;maxWidth=300;quality=90)